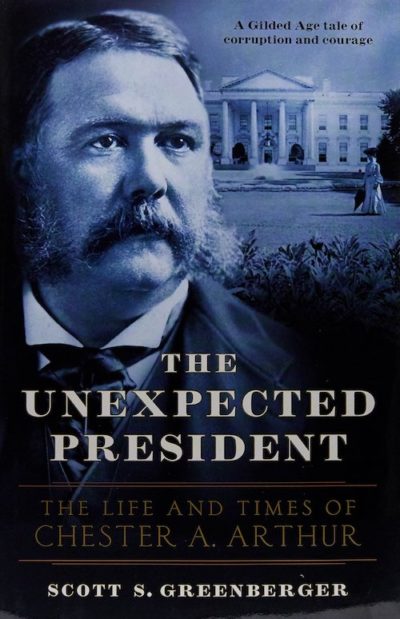

The Unexpected President

by Scott S. Greenberger

The Unexpected President: The Life and Times of Chester A. Arthur

by Scott S. Greenberger

304 pp., Da Capo Press

$14.99

Few anticipated Vice-President Chester Arthur—a son of an ardent abolitionist preacher and progeny of the powerful New York Republican political machine—would ever become president. Even less suspected he would turn into a balanced and principled chief executive who would eschew ideological paradigms to push progressive policy. He had been selected as James A. Garfield’s running mate in the 1880 presidential election, to appease the Stalwart (anti-civil service reform) wing of the Republican Party that feared Garfield’s progressivism, and who foresaw his presidency as a “‘national calamity’” that would retard reforms (Greenberger, p. 161).

Scott Greenberger’s “The Unexpected President,” utilizes prolific primary source evidence– private letters and newspaper clippings– to assiduously detail the transformation of Arthur from a cog in the New York Republican patronage machine to a president who signed and vigorously enforced the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act that initiated true civil service reform and “restored Americans’ trust in their government” (Greenberger, p. 224). The author’s well-written account of the about-face of one of America’s “most obscure chief executives” reveals that politicians are not always bound by the political and moral realities of their time. And, he reminds Americans of a pivotal president who—though hailed at his death as an “‘historic man’”—has been all but forgotten (Greenberger, p. 238).

The first several chapters describe Arthur’s early life and his key influences. He was the son of William “Elder” Arthur, a fiercely moralistic abolitionist preacher who unwaveringly defended his beliefs, even when he was exiled from several Northern parishes and faced political violence (Greenberger, p. 9). After graduating from the prestigious Union College, Arthur had no clear intention of entering politics. Beginning his career as a New York lawyer, Arthur garnered attention for successfully representing a black woman who was forcibly removed from a streetcar. The ensuing case, Jennings v. Third Avenue Railroad Company, initiated the desegregation of all New York streetcars (Greenberger, p. 24). Soon after, he became engaged to Dabney “Nell” Herndon, a Washington socialite, and daughter of a renowned sea captain.

The next several sections detail how, Arthur became politically active. His motivation was to advance his social and financial status at any cost, as “business and politics were being braided together” in New York (Greenberger, p. 41). As the protégée of New York Whig (later Republican) boss Thurlow Weed, Arthur became connected with Edwin Morgan, the man elected governor of New York in 1860.

As his political career ramped up, Arthur’s morality diminished–drastically. In Greenberger’s view, he “no longer viewed politics as a struggle over issues or ideals . . . [but as] a partisan game, and to the victor went the spoils” (Greenberger, p. 75). Arthur declined to re-join the Army after he lost his political appointment as a general in the New York militia. Greenberger contends this decision was partially driven by Arthur’s objection to President Abraham Lincoln’s abolitionist war goals; by then, Arthur was concentrating on his mercenary mission to exploit his military connections to lobby for prolific wartime industrial contracts “to get rich” and satisfy his social ambitions. (Greenberger, p. 55).

Eventually, Arthur “embraced Weed’s approach to politics”—exchanging government jobs for political support (patronage) (Greenberger, p. 44). Greenberger recounts how Arthur’s political association with a subsequent New York Republican boss named Roscoe Conkling, greased his appointment to Collector of the Port of New York– a lucrative position, financially and politically. Arthur made about a million dollars (in today’s dollars) from salary, expediting imports for prominent officials, and late nights filled with drinking and gambling. With it, he was limbered up to bring home a lavish lifestyle for Nell. (Greenberger, p. 80).

Arthur dispensed Customs House jobs to political supporters, and ensured they supported Republican campaigns by refusing to faithfully enforce the new civil service reform rules. Although he was required to create a civil service commission for hiring, he picked “three good friends, all of them party workers” to run it (Greenberger, p. 84). The hiring exams “were a farce”, because Arthur circulated the test answers to his preferred candidates.

Throughout his description of Arthurs’s pre-presidency years, Greenberger, a veteran political journalist who holds degrees in history and international affairs from Yale and George Washington University, astutely articulates the case against the patronage Arthur practiced, asserting that its use (by both parties) “corroded Americans’ faith in their government” and “twisted [democracy] into a game of place and [party] power” (Greenberger, p. 43).¹ Still, this is a balanced book. Greenberger acknowledges the opposing view held by political machine leaders– and some workers– that the jobs political leaders dispensed through the “fair and democratic” spoils system provided many people with a “steady salary and a sense of identity” (Greenberger, pp. 42-43).

Ironically, when Arthur inherited the presidency after Garfield’s assassination, he took a decidedly different direction. Greenberger ultimately argues that “watching Garfield’s long ordeal” of an agonizing death “greatly affected Chester Arthur” and sobered him into “contemplat[ing] his own history” (Greenberger, p. 182). The expanse of his feelings is unknown. Arthur had an aversion to the media, and at his request, most of his personal papers were destroyed, posthumously. (Greenberger, p. ix).

Still, Arthur’s transformation is evident in his actions. He vetoed an initial version of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred most Chinese from gaining American citizenship, and backed naval modernization. Upon assuming office, he also broke with Conkling and the Stalwarts by refusing to replace Garfield’s choice to head the New York Customs House with a Stalwart, as he felt “‘morally bound’” to continue Garfield’s policies (Greenberger, p. 182).

Arthur also revived the stalled push for civil service reform by declaring his support for it. With his backing, the Pendleton Act was passed. Arthur signed and implemented its “regulations with vigor” (Greenberger, p. 216). As the central aspect of Arthur’s political immorality had been his embrace of patronage and pursuit of politics over principles, his politically perilous advocacy for civil service reform as president was the hallmark of his administration—but it cost him the 1884 nomination.

Behind Arthur’s metamorphosis, Greenberger suggests a surprising catalyst. A young, invalid woman named Julia Sand dispatched letters to Arthur, regularly, urging him to seize his “‘spark of true nobility’” as president and “‘reform’” (Greenberger, p. 108). Greenberger presents some of her letters, which counseled Arthur about the feelings among the American people, and urged him to pursue certain policies. Sometimes, his actions dovetailed with her advice (as with civil service reform). For evidence of her influence, Greenberger recounts a visit the now widowed Arthur made to her home, and how he saved her letters—even after he burned many others.

Readers should take this story with a grain of salt, however, as it is impossible to know the degree to which Sand’s letters actually moved Arthur. Greenberger acknowledges that Arthur’s and Sand’s meeting, in the presence of her family, was “uncomfortably stiff” (Greenberger, p. 202); it is unclear if Arthur responded to her important letters, but her later correspondence expressed her disillusionment, because—as she saw it—her advice was being ignored:

Invalid as I am, for more than a year I have poured out my best strength in one contentious appeal to your finer nature—& what has it availed? The dew might as well fall on polished marble in the hope of producing a flower (Greenberger, p. 205).

Regardless, Greenberger’s presentation of Sand’s letters is an empowering story of how an everyday grateful American—a lady living in an era in which women were largely “excluded from public life” (Greenberger, p. 167)—drew the attention of the president of the United States with her unbridled belief that power should—and could—be used for the common good.

Although this book is chiefly Arthur’s, it is also an excellent primer on the history and politics of post-Civil War America. It is an incisive work about a man who unexpectedly defied the very corruption that helped catapult him to the presidency.

This story is particularly relevant in an era of faltering faith in politicians to do the right thing, in a democracy many Americans believe is distorted by large campaign donations.² Full of lessons for history buffs—or not—I wholeheartedly recommend this book.

Quentin Levin is a college student majoring in Communications, Law, Economics, and Government and is passionate about history.

1. “Scott S. Greenberger. The Pew Charitable Trusts. Accessed 29 Dec. 2018.

2. Jones, Bradley. “Most Americans want to limit campaign spending, say big donors have greater political influence.” The Pew Research Center, 8 May 2018.