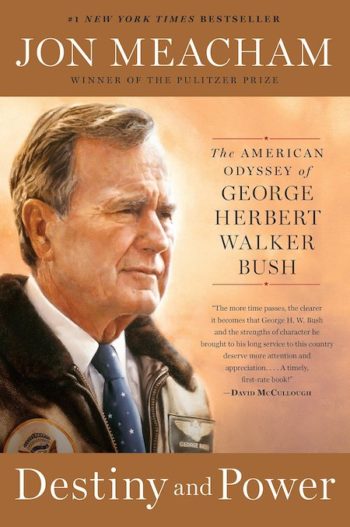

Destiny and Power

The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush by Jon Meacham

Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush

by Jon Meacham

864 pp., Random House

$35

President George Herbert Walker Bush’s passing represented a style of leadership that Americans once took for granted. Born to a wealthy Massachusetts family in 1924, he embraced—early on–the belief that privilege entails responsibility. As a U.S. Navy airman, businessman, and politician, Bush sought distinction within the framework of a firm moral code that demanded integrity, courage, and dignity. This mindset tempered and provided focus to his passionate and decades-long pursuit of the presidency. The tragedy of George H.W. Bush’s odyssey is that his personal code of conduct–so worthy of the greatest of his predecessors–eventually contributed to his political downfall.

Jon Meacham’s epic biography begins by placing Bush squarely among the New England elite families to which both of his parents, Prescott S. Bush and Dorothy Walker, belonged. He was bred to lead. At home and at school, from Phillips Academy in Massachusetts, to Yale University, Bush learned to love the thrill of competition, and the satisfaction of achievement. He also imbibed a strong sense of personal duty to family, God, and country.

When the United States entered World War II he enlisted without hesitation, and served with honor. In September 1944, Lieutenant Bush piloted an aircraft in an attack on a Japanese military installation. Hit by flak and with his plane on fire, Bush nevertheless successfully hit his target and then bailed out. His two fellow crewmen perished, but Bush endured several hours at sea in a flimsy life raft before an American submarine rescued him. The memories of this and other experiences would endure to the end of his life.

Returning from the Pacific theater, Bush married his sweetheart and lifelong companion, Barbara Pierce. The couple moved to Texas, where he worked his way up from the very bottom rung to become a successful businessman in the oil industry. But, politics beckoned, and following the example of his father Prescott, who served as a U.S. senator from 1952-1963, George H.W. Bush was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1966. Father and son were Republicans during the Dwight D. Eisenhower era, and they looked to Ike for political inspiration. George’s ambitions were high, and–from the very beginning–he sought to become President of the United States.

Meacham’s narrative follows Bush’s slow and not always steady rise through the American political system over the ensuing decades. After unsuccessfully running for the senate, Bush served in the 1970s under presidents Richard Nixon (who remained a lifelong correspondent) and Gerald Ford as Ambassador to the United Nations; Chairman of the Republican National Committee; Liaison to China; and Director of the C.I.A. In 1980, feeling that his political time had finally arrived, Bush sought his party’s nomination for the presidency, only to run into the juggernaut that was Ronald Reagan. After a tense campaign, the two put aside their differences and formed a powerful ticket that secured the presidency for Reagan.

As a vice president who fully intended to run for the presidency again, Bush was to some degree stuck betwixt and between. He decided from the very beginning to maintain absolute loyalty to President Reagan despite Bush’s somewhat more moderate political beliefs. This cast Bush into a very deep shadow from which he struggled to emerge—this despite the poise with which he carried himself during the attempted assassination of Reagan in March 1981, and his yeoman’s work as a diplomatic envoy. By 1988, the public, the media and his fellow Republicans struggled to understand what Bush stood for. Was he just an eastern elite seeking power for its own sake? A Reagan cipher? A “wimp”?

Bush’s greatest assets as a leader—his integrity, and his desire to place sound policy before ideology—were political liabilities in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Meacham, who honestly assesses his subject’s strengths and weaknesses as a politician, reveals the reluctance with which Bush accepted the aggressive campaign strategies advocated by managers Lee Atwater and Roger Ailes. Negative ads—which as Meacham points out were consistent with what other candidates had used since the 1960s—and bold promises such as “no new taxes” helped win Bush the presidency over Democrat Michael Dukakis. But they also foreshadowed for his subsequent defeat against Bill Clinton, who was a very different kind of campaigner.

The successes of Bush’s administration–his careful handling of the collapse of the Soviet bloc and his steady leadership in the 1990-91 war with Iraq—for example, were quickly forgotten in the wake of his decision to introduce new taxes despite his campaign pledge. Bush accepted what he knew could amount to political suicide because he believed that it was the right thing to do for a country in pursuit of a balanced budget. Besides, with a solidly Democratic Congress, he had few choices beyond cooperation and compromise. Ironically, as Meacham shows, Clinton would reap an additional reward with his 1992 triumph: the opportunity to preside over a balanced budget at a time of enormous prosperity.

The only drawback to Meacham’s otherwise masterful and compulsively readable biography might arise from George H.W. Bush’s strangely enigmatic political personality. Readers will gain a strong appreciation for Bush’s personal character, and a detailed understanding of his rise to, and exercise of power. The how and what, though, do not answer a multitude of whys. Why did Bush become a Republican? Why, for example, did he align himself with conservative Barry Goldwater in 1964, but then vote for the Fair Housing Act in 1968 and subsequently portray himself as a moderate Republican? Most important, why did he seek to become president, and what did he hope to do beyond charting a steady course?

Bush’s critics accused him of lacking firm political convictions. Meacham refutes the criticism, probably rightly, but not terribly effectively. A deeper investigation into Bush’s thoughts on history, economics, foreign relations, and public policy—surely possible given that he was a well-read and intelligent man—would do much to reveal the inner qualities of a man who set an example for honorable and selfless leadership.

Ed Lengel is an author, a speaker, and a storyteller.