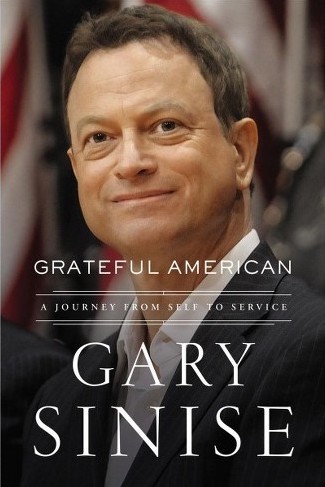

Grateful American: A Journey from Self to Service

by Gary Sinise

Grateful American: A Journey from Self to Service

by Gary Sinise with Marcus Brotherton

272 pp., Thomas Nelson

$17

“Lt. Dan” chronicles his transformation into real-life military advocate.

Fifty years ago, President Lyndon Johnson was fired from his job. America — and its youth — was saturated with years of “progress” reports about Vietnam that turned out to be false.

In a deep upsurge of anti-establishment rage, manifested in marches, moratoriums, and mass protests, Johnson was swept from the White House and returned to his Texas ranch. He was replaced by Richard Nixon, who punctuated his presidency with promises, promises of peace that were premature.

Meanwhile, somewhere in the vortex of the country-wide commotion, a 14-year-old boy in Chicago was skipping classes, pulling pranks, partying with his buzzed bandmates, and absorbing the way-out wisdom of the Who, Jimi Hendrix, Crosby, Stills & Nash, the Beach Boys, Led Zeppelin, and Peter, Paul and Mary. According to Gary Sinise’s memoir, Grateful American: A Journey from Self to Service, the actor implies that his developmental zigzag to maturity might have been caused — partially — by the dynamic in his home:

Reading and writing didn’t come easily to me…Today they’d probably diagnose some kind of learning disability. But maybe I just never learned the fundamentals. Mom…carried a load at home…raising three kids…taking care of her mother and…sister…and I think Dad probably overextended himself financially, and that’s why he worked all the time.”

A face-off with flunking out seemed fated, but serendipity disguised as a drama teacher defied the debacle-in-the-making:

She walked straight toward us, a teacher named Barbara Patterson. She was a powerhouse of a gal, a tornado of a woman…She slowed when she neared us, stopped, and gave a diminutive sniff. Our clothes were cool and raggy, and my bandmates and I…wore scruffy jackets. I’d let my hair grow crazy and curly…She looked at us and said, ‘I’m directing West Side Story for the spring play. You guys all look like you could play gang members.’”

Sinise got the part of Pepe, a minor delinquent, and — to his amazement — he relished the five-week ramp-up to assimilate into the role; he formed friendships with the cast and, for the first time, attracted some auspicious academic attention:

Teachers noticed this genuine change in me. In English, Mr. Allison knew I sucked at taking exams, but one afternoon he…asked me to tell the class what had been happening in play rehearsal. I didn’t normally speak up in class. Ever. But on the spot I opened up and told everybody about the play. My words were enthusiastic, my voice clear…I was surprised later when Mr. Allison handed me a solid grade for ‘giving an oral report.’”

By the time Sinise graduated in 1974 — half a year behind his peers because of a deficiency in credits — he had excelled in all of his drama classes and garnered leads in the school’s productions of “Tartuffe,” “Guys and Dolls,” “Look Back in Anger,” and “A Thousand Clowns.”

Almost immediately, he pushed aside the possibility of college in favor of presenting “And Miss Reardon Drinks a Little” in a Unitarian church:

During rehearsals, we got ready to print programs and I said, ‘Okay, we need to call this outfit something.’ We threw out all kinds of names. Rick [actor-friend] was reading a Hermann Hesse novel called Steppenwolf, and while everyone was making suggestions, he didn’t say anything. He just held up his novel, and pointed to it, and I said, ‘Great, Rick! Let’s put that on the program.’ I hadn’t read it, but it sounded good. Steppenwolf Theatre Company. We needed to print programs quickly, so Steppenwolf it was.”

Two years later, the theater was incorporated by its founding members, Sinise, Terry Kinney, and Jeff Perry, with a resident company that included John Malkovich, Laurie Metcalf, Moira Harris, and Alan Wilder. Later, Joan Allen, John Mahoney, Dennis Farina, and others joined. Careers were carefully crafted, and “Steppenwolf” — an artistic Armageddon — eventually achieved accolades, awards, and appreciative audiences all over the world.

Sinise sometimes doubled as the artistic director; he was prolific and parsimonious in his productions, which had been limited to Chicago until he bucked the board’s objections, staged Sam Shepard’s “True West” in New York, and won an Obie for directing.

Sinise succeeded logistically, but he was outmatched by Malkovich in performances, which were quickly praised by critics, celebrities, and customers. Soon, Malkovich was parceled and packaged by powerful agents, who managed media interviews and catapulted him to A-list movies and the covers of high-gloss magazines.

Sinise, in contrast, remained underutilized — until he was picked to play Lt. Dan Taylor, “a disabled Vietnam veteran who loses his legs in combat,” in a movie called “Forrest Gump.” He was nominated for an Academy Award for that portrayal, which remains the role for which Sinise is known — and revered — throughout the world.

The brutal boot-camp-like preparation required to “become” Lt. Taylor propelled Sinise from a focused, assiduous actor into a serious armed-forces activist. After 1994’s “Gump,” he participated in USO-sanctioned entertainment junkets, visited war-zone hospitals overwhelmed by suffering soldiers, and appeared at fundraisers on behalf of veterans organizations:

I knew something big was shifting inside of me. A transformation was now under way. I was no longer primarily an actor…I was becoming an advocate…my job was to carry a nation’s gratitude to the troops.”

Since 2004 — between gigs in “Apollo 13,” “Truman,” “Ransom,” “George Wallace,” “The Green Mile,” and “CSI: NY” — Sinise and his “Lt. Dan Band” have performed more than 400 concerts for half a million soldiers at military bases from Iraq, Afghanistan, and Kuwait to Japan, Korea, and Guantanamo Bay. Seven years ago, he founded the Gary Sinise Foundation, which supports and strengthens programming at more than 30 serviceperson institutions.

Sinise has been magnificently magnanimous to the sometimes taken-for-granted soldiers, an irony — especially during a time of prickly politics, demographic divisions, and willful warmongering.

I wanted to let them know the country…hadn’t forgotten them…And we wouldn’t forget…not ever…if I could help it.”

David Bruce Smith is also a grateful American, the author of 11 books, and founder of The Grateful American Foundation, which is celebrating its fifth year of restoring enthusiasm about American history for kids — and adults — through videos, podcasts, and interactive activities, and The Grateful American™ Book Prize for excellence in children’s historical fiction and nonfiction focused on the United States since the country’s founding.

Read the original review in the Washington Independent Review of Books >>