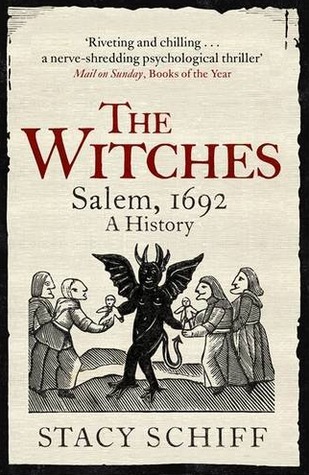

The Witches; Salem, 1692: A History

by Stacy Schiff

"The Witches; Salem, 1692: A History"

by Stacy Schiff

417 pp., Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2016

Growing up in Salem, Massachusetts, my first job aged 14 (not including a stint as a diminutive paper girl) was to serve as a tour guide at the Witch House, home to Jonathan Corwin, one of the witchcraft judges.

Later in high school, I transitioned to the pinnacle of Salem tourguiding, the House of Seven Gables. This 17th century house on Salem Harbour, owned by the cousin of Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864), was a place of refuge after the death of Hawthorne’s father when he was four years old. His memorable visits inspired Hathorne to use it as the setting for his 1851 romantic tale of the same name in which the main characters fall in love – one a descendant of a witchcraft judge, and the other of a witchcraft defendant whom the justice had sentenced to death. It was an imagined rectification of Hawthorne’s personal history. His ancestor was John Hathorne (1641-1717), whose punitive interrogation of witchcraft suspects contributed to the death of twenty-four. Lore has it that Hawthorne added the ‘w’ to his name to disassociate from the sins of his forbearer, which included Hawthorne’s refusal to give a public apology before his death.

Armed with this background – augmented by my experience of having a Salem classmate whose mother was Laurie Cabot, still today “The Official Salem Witch” (who was not always useful to the Boston Red Sox who called on her services, still working then to fend off a curse for having traded Babe Ruth to the New York Yankees in the early 20th century); familiarity with the sites around town known for witchcraft association—such as Gallows Hill—where the hangings allegedly happened; being a member of The Witches as the local high school’s clubs and sports teams were called; and the sheer cool factor of trick or treating in Salem during my childhood Halloweens – I thought there was little I could learn in reading Stacy Schiff’s, The Witches.

I was wrong.

Schiff masterfully wades through the diaries, court transcripts, letters and other extant literature to reveal the backstories of victims, illuminating a confining, superstitious and unforgiving climate in Puritan New England which led to tragedy –in the form of death to innocents, but—also—devastation to those left behind.

It was not particularly auspicious to be born in 17th century Salem. Though Salem Town and Salem Village, with a burgeoning population of nearly 2000 in 1692, were important for commerce (Town) and farming (Village) – Boston had more than triple the number with 7000 inhabitants (by comparison, there were over 100,000 in London across the sea) – there was little time for leisure, though Schiff notes a fair number of taverns in Salem and its environs. For adults and children non-Sabbath days were long and Sabbath days longer in the very cold winters, and stifling summer churches. Life was not especially easy in the Bay Area for other reasons: Massachusetts had lost its independent charter a few years before and inhabitants lived in a milieu of fractious politics and frequent disputes over land, livestock and even ministers.

Schiff writes that servant girls were particularly unfortunate. “For reasons that made sense at the time but have not been adequately explained since, a third of New England children left home to lodge elsewhere, usually as servants or apprentices, often as early as age six.” “Servant girls,” she says, “fended off groping hands and unwanted embraces” and far worse from heads of households and other men with whom they came in contact. “Masters and mistresses beat servant girls for being disrespectful, disorderly, abusive, sullen…for crimes no greater than laziness, which – given the amount to be done – was surely a relative term.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, nearly half of the bewitched girls were domestics (and Schiff indicates that a majority of the bewitched girls had lost fathers). Despite humble personal means, Schiff indicates that they sought protection from the courts and “More often than not rulings came down in the favor.” There was thus legal precedent for yielding to the testimony of young women without social standing, even when, in the case of Salem 1692, they were deluded at best or criminal at worst.

Witchcraft was a thing in 17th century New England. After idolatry, so abhorrent in the stripped- down version of Christianity proffered by Puritans, the second crime in the legal code was witchcraft. In the absence of the scientific method, pursued nearly a century later by Massachusetts’ son Benjamin Franklin among others during the Enlightenment, colonists enshrined in 1641 law that “If any man or woman be a witch, that is, hath or consulteth with a familiar spirit, they shall be put to death.”

But such was the power of the Salem witchcraft legend, I was unaware of earlier instances of apparent devilish dealings in 17th century New England that Schiff highlights. Connecticut, no less, had put a number of its citizens to death 30 years earlier and might well have claimed Salem’s modern tourism dollars. But justices elsewhere proceeded generally with greater caution than they would in Salem. Accusers were subject to whipping for false testimony and the accused fined for lying. Schiff cites 103 witchcraft cases prior to 1692, 25% of which were successfully prosecuted.

Along with meagre belongings, pilgrims landing at Plymouth Rock brought tales of witchcraft from the mother country, Scandinavia, and the Continent. Witches and their practices were as much a part of local conversation as rampaging natives, brutal weather and other things that darkened Puritan skies. Illness–and worse death—plus other things that could not always be easily explained might be attributed to spectral wanderings and demonic acts. In the climate painted by Schiff, 1692 Salem seems less an outlier than an inevitable result of a culture squeezed by harsh beliefs and circumstance.

It was in the household of persnickety Salem village minister, Samuel Parris, that it all began in the depth of a January winter. His 11-year-old niece Abigail Williams and nine-year-old daughter Betty began to exhibit worryingly similar symptoms: they “barked and yelped” and fell dumb while their “bodies shuddered and spun.” They complained of bites and pinches by ‘invisible agents.’ They made utterances without meaning where before they had been model children. It seemed familiar to the young minister, Cotton Mather, who comes across in Schiff’s telling as a pompous, fastidious, fame-seeking meddler (who out-manoeuvred his Minister father, Increase Mather, then urging circumspection over cries of witchcraft). He had observed a similar manifestation in the previously stalwart children of a pious Boston stone layer. Those children appeared most afflicted when Mather attempted Biblical intervention. Reverend John Hale who examined the beleaguered girls recorded that the ‘evil hand’ was the finding espoused by the neighbourhood. And if that was so, whose was it? Schiff’s text is filled with wry observations, including that a good haunting could make unending task-filled days less dull. Before long other girls became afflicted. The next two were twelve-year-old friend Ann Putnam Jr. and Elizabeth Hubbard, niece of Abigail and Betty’s attending physician.

Soon a witch was found: “semi-itinerant beggar” Sarah Good, a figure of menace for the community who “would seem to have wandered into the village directly from the Brothers Grimm, were it not for the fact that they had not been born yet.” Raised in prosperity, dissipated by fate, she was brought to a makeshift court where Corwin and Hathorne presided. ‘Sarah Good,’ the latter asked, ‘what evil spirit have you familiarity with?’ ‘None,’ she replied curtly. Not satisfied, he pressed further, was she in league with Satan and why had she hurt those children? All four of the affected girls were present and testified that Good was responsible for their pain and disquiet; they writhed and choked as they passed in front of her (attending trial absolved one from household chores and other tedium). Hathorne demanded, ‘Sarah Good, do you not see now what you have done? Why do you not tell us the truth?’ Why do you thus torment these poor children?’ Tartly Good replied something had afflicted them all right, but it was not her. Aware that Hathorne had approved two other arrests – Sarah Osborne, a chronically ill villager who’d also fallen on hard times, and the Parris household’s West Indian slave Tituba – and worn down by Hathorne’s badgering, Good named Osborne. Despite baiting by Hathorne when called before the crusading judge, Osborne refused to name Good in return (he also chided her for not attending church, which she attributed to her maladies). With forbearance Osborne declared, ‘I do not know the devil.’

Tituba, however, wasted no time in concocting a tale she thought the judges might like, enjoying her brief celebrity. Perhaps recalling folk stories from Barbados, the island from which she likely hailed, Tituba told of wondrous things, making clear, according to Schiff, “that she must have been the life of the corn-pounding, pea-shelling Parris kitchen.” So engrossing was her story, the girls stopped their contortions to listen carefully: a wily Sarah Good had appeared before her with a menagerie that included a yellow bird and two red cats enjoining her to torment the girls. She remembered encounters with dark lords and flights by pole, accompanied by Good and Osborne, across the Salem firmament. All four women were interned in a Boston jail.

But in a strange twist on the typical workings of justice, Schiff records that those who confessed were imprisoned, but not killed. Osborne died chained in her cell before she could be sentenced while Good was hung by the close of July. Tituba, the girls and soon many others, wittingly or not, played a deadly game. Her colourful yarn all but forgotten, Tituba languished in prison (a soul-crushing dank, rodent-infested, disease-ridden place where three other accused died before they could be tried, sentenced or pardoned) – until someone in 1693 paid bail to free her, after which she was lost to history.

Lost, but not to history, were nineteen others – in addition to Good – whose lives ended on the gallows. Thirteen of them were women; it was risky to be female during a witchcraft epidemic. Among the males hung was Minister George Boroughs, who—along with other suspicious characteristics– was preternaturally strong. But, strength did not help him, nor did it benefit Giles Corey, who by refusing to enter a guilty or innocent plea, was pressed to death. Such was the penalty at that time and place (Corey had accused his wife of witchcraft, too much unexplained night time activity; she was among the women hung). Schiff uncovers the existence of sceptics like Thomas Brattle, an “accomplished scientist and logician,” but they were too few.

Inhumanity – confinement, little rest, limited nutrition and constant harassment and abuse – can do strange things to the human brain.In Salem, there was much corroboration among witchcraft accounts of both the accused and accusers. Schiff notes that 50 confessed; a number of them cited a kind of witchcraft jamboree in Samuel Parris’ pasture, presided over by Reverend Burroughs during which “the devil offered his great book, which all signed, some in blood.” Accused and accusers and judges were frequently related. In the different permutations of accusation, daughters accused mothers and husband’s wives; only sons did not accuse fathers.

Things came to a head when the unpopular, Crown-appointed Governor, Sir William Phips, who helped at least one set of accused friends escape from Massachusetts, halted further arrests in October 1692, not least because his wife had been named. By November, he disbanded the damning witchcraft court of Oyer and Terminer, comprised of overzealous judges like Hathorne; Waitstill Winthrop (who should have taken his first name to heart); and Lieutenant Governor William Stoughton. To their dismay, it was before they had resolved questions about the role of spectral evidence, swimming trials, witch marks, and touch tests to discern the guilty.

Upwards of 150 were accused. (Not much is said about the two dogs put to death for complicity.) The youngest was five-year-old Dorcas Good, orphaned when her mother Sarah was put to death. She remained shackled in prison for some 8 months; forever after, according to the Salem Witch Trials Reader (2000), she lived in fear and never independently. She was not the family’s only casualty: Sarah Good was pregnant when incarcerated; her daughter Mercy was born and died in captivity some time before her mother’s execution.

Lives were ruined in other ways. Justice Corwin’s twenty-five-year-old nephew, County Sherriff George Corwin, “wore himself out dismantling the households of the accused.” Schiff notes the Sherriff even removed the gold wedding ring from the mother of one of the convicted. Victim’s families frequently found themselves with little, making it even more difficult to regroup and rebuild.

Schiff’s work is densely packed like a deliciously rich fruitcake. But chapter subsections would have made for easier reading. That said, the close texture of the paragraphs builds to an “oppressive, forensic, psychological thriller: J.K. Rowling meets…Stephen King,” according to London’s The Times.

In the end, was it hysteria, mouldy food, jealousy, boredom or something else that had led to disaster? As Schiff cogently says, “Antipathies and temptations are written in invisible ink; we will never know. …Witchcraft localized anxiety at a dislocated time.”

Prolific accuser, Ann Putnam Jr., thought she knew: she had made it up. (While she enjoyed the attention of the community, sixty-two people had afflicted her and of the nineteen hanged, she testified against all but two.) Schiff sets the scene for her 1706 confession: not yet 30, she stood silently before her Salem Village congregation as a minister read out her words. She asked for forgiveness. She had not acted alone. But in her defense, she posited she had been unable ‘to understand, nor able to withstand, the mysterious delusions of the powers of darkness and Prince of the air.’ Salem and shadowy things had not quite had their curtain call as I discovered in my youth.

Dr. Marcia Balisciano is Director of the Benjamin Franklin House in London.