The Rhyme of History: Mark Twain

Special to the Newsletter

by Michael F. Bishop

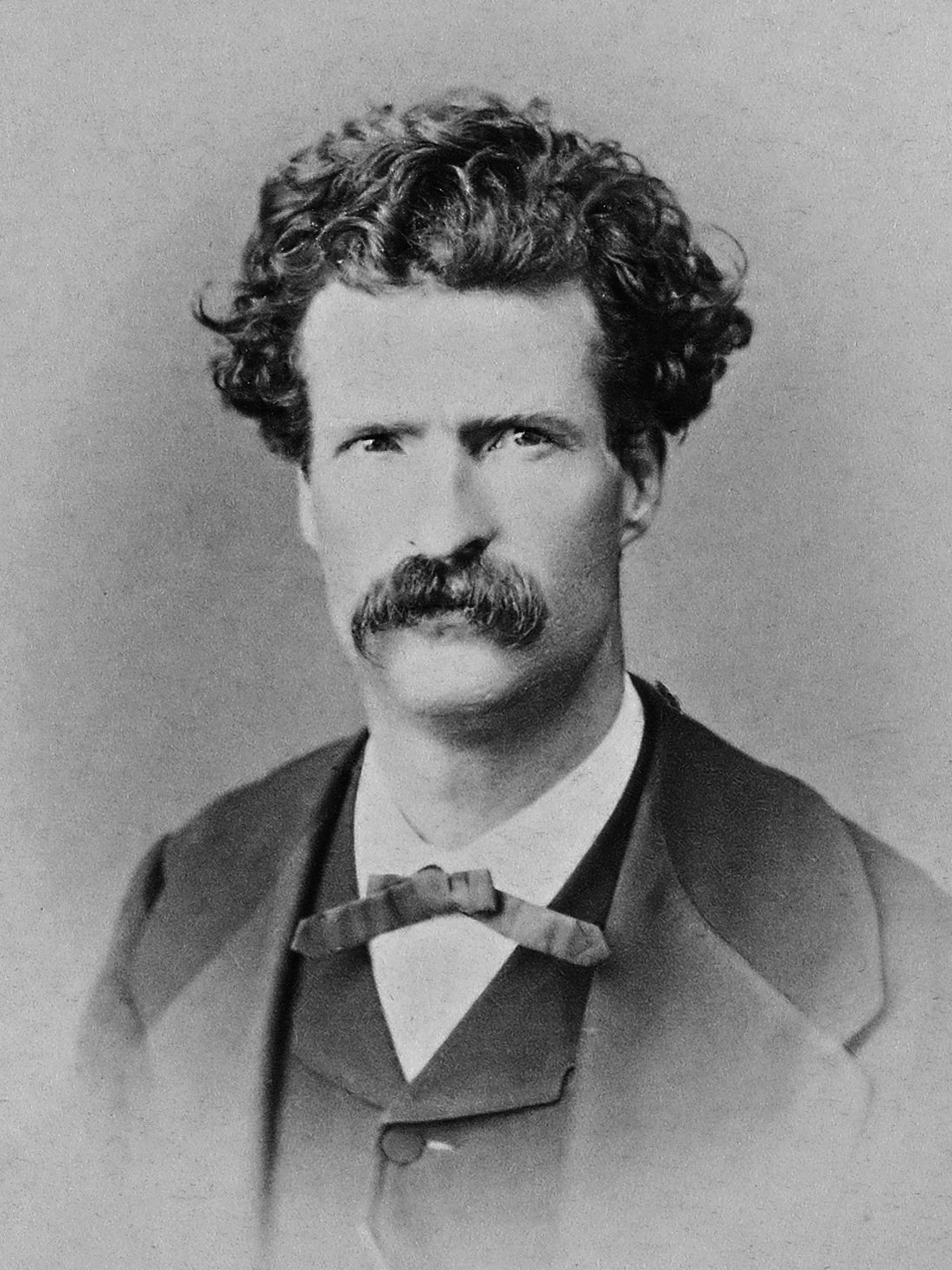

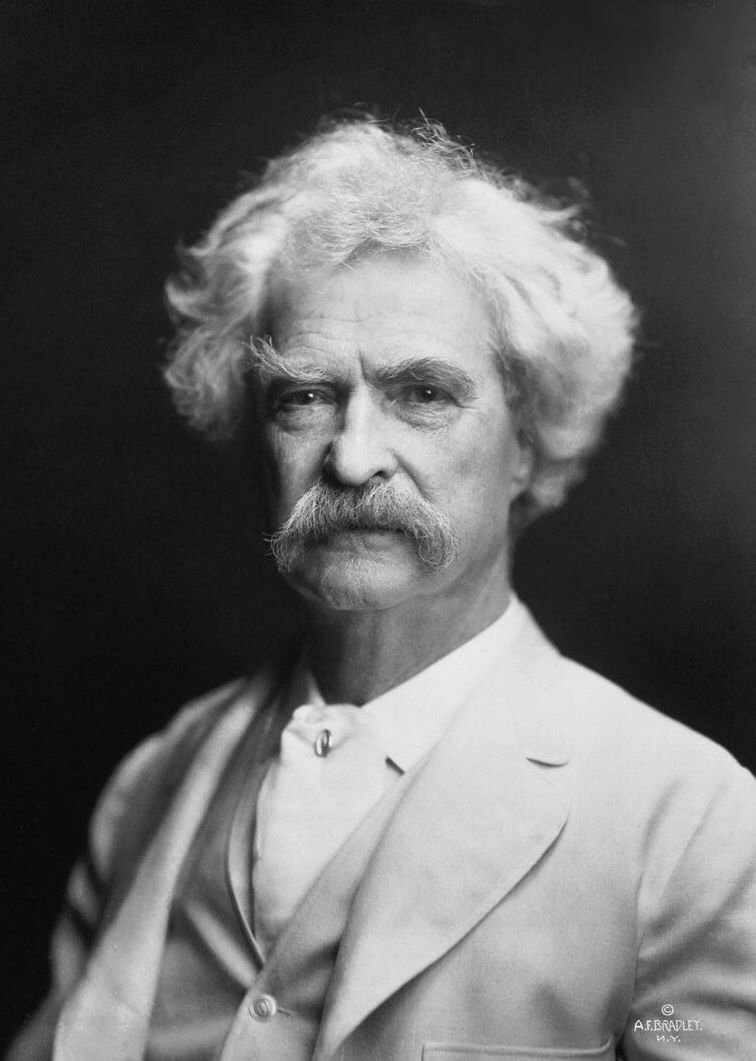

Mark Twain, the white-suited, white-haired, and cigar smoking giant of American literature, rivaled his contemporaries Oscar Wilde and Benjamin Disraeli in the art of the aphorism. He advised young people, “Always respect your superiors, if you have any” and observed, “Man is the only animal that blushes. Or needs to.” He is also credited with the observation, “History does not repeat itself, but it rhymes,” which may be filed under the category of “too good to check.”

Twain, Age 31

Samuel Langhorne Clemens was born on November 30, 1835, in Florida, Missouri. The Mississippi River shaped his early years, it was the mighty waterway which would course through his life. His family moved to Hannibal, Missouri, when he was four, a river town that became the inspiration for the fictitious St. Petersburg in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Twain was the sixth of seven children, though only three survived childhood. His father, John Clemens, an unsuccessful businessman, died when Clemens was 11, plunging the family into penury. This forced young Samuel to leave school and take up work as a printer’s apprentice, an immersion in the printed word that would change his life—and—American letters.

By his late teens, Clemens was setting type for newspapers, including his brother Orion’s Hannibal Journal, where he began dabbling in humorous sketches. Restless and ambitious, he left Hannibal at 17, working as a printer in cities like St. Louis, New York, and Philadelphia. But the Mississippi River called him back. In 1857, he was apprenticed as a steamboat pilot and earned his license two years later. The river taught him the rhythms of life—its beauty, danger—and unpredictability—and—gave him his pen name: “Mark Twain,” a riverboat term meaning two fathoms deep. The Civil War halted river traffic in 1861, but the river’s imprint on his life endured.

He briefly joined a Confederate militia, an episode he later recounted with self-deprecating humor in “The Private History of a Campaign That Failed,” before deserting after two weeks. Seeking fortune, he went to Nevada. There, Twain tried mining during the silver rush but found greater success with his pen. In 1862, he joined the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise, where his sharp, irreverent style flourished. He then moved on to San Francisco, where he honed his craft as a freelancer.

Twain’s national breakthrough came in 1865 with “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County,” a tale of a rigged frog race that highlighted his knack for blending humor with human insight. Published in New York’s Saturday Press, it catapulted him to fame. In 1867, he leveraged this success into a lecture tour and a travel assignment aboard the Quaker City to Europe and the Holy Land. The resulting book, The Innocents Abroad (1869), was a bestseller, satirizing American tourists and European pretensions.

That same year, Twain met Olivia “Livy” Langdon, a delicate, intelligent woman from a wealthy New York family. Despite her frailties, she had been injured as a teen and suffered chronic illness—they married in 1870. Livy became his emotional anchor and editor. They settled in Buffalo, then Hartford, Connecticut, and had four children. Their home, a vast, Gothic mansion, reflected Twain’s flair and success.

Twain joined the literary immortals in the 1870s and 1880s. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) captured boyhood with nostalgic charm, drawing from his Hannibal days. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), his masterpiece, tackled slavery and morality through Huck’s journey with Jim, a runaway slave. Its vernacular style and unflinching social critique made it revolutionary, though its raw language later made it controversial in our more sensitive (or just censorious) age. Twain also penned The Prince and the Pauper (1881) and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889), blending satire with historical fantasy.

In 1885, he had the inspired idea to encourage General Ulysses S. Grant, who had lost his post-presidential fortune to an unscrupulous business partner, to write his memoirs of the Civil War. The resulting volumes, published by Twain, saved Grant’s family from ruin and swelled the coffers of Twain’s publishing firm, Charles L. Webster & Co.

Yet for all his literary success, Twain was an uncertain businessman. He made a large and ultimately ruinous investment in the Paige Compositor, a typesetting machine that promised to revolutionize printing, but it never worked reliably. By 1891, his debts forced the family to move to Europe; his publishing firm collapsed three years later, and at 58, he faced bankruptcy.

With grim determination, he embarked on a grueling worldwide lecture tour from 1895 to 1896, regaling audiences with tales and quips from Cleveland to Cape Town. The tour paid off his debts. Following the Equator (1897), a travelogue from this journey, blended humor with sobering reflections on imperialism.

Twain’s later years were darkened by loss. His wife and three of his children predeceased him. These tragedies stoked his late works’ bitterness—unpublished works like The Mysterious Stranger bristled with disillusionment. Yet his writing continued, including his sprawling Autobiography, and essays on politics and religion.

Twain in 1907

Publicly, Twain remained a beloved curmudgeon and a cultural icon. He sparred with Teddy Roosevelt, critiqued American imperialism, and championed women’s suffrage. Oxford awarded him an honorary degree in 1907, a rare nod to a self-educated man.

Twain died of a heart attack on April 21, 1910, in Redding, Connecticut, at the age of 74, just as Halley’s Comet—which had blazed at his birth—returned. He had predicted this celestial timing, joking he’d “go out with it.” But his reputation would remain among the stars.

Michael F. Bishop, a writer and historian, is the former executive director of the International Churchill Society and the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission.