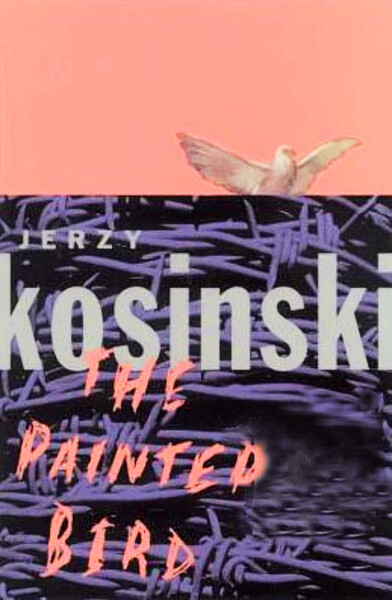

The Painted Bird

by Jerzy Kosinski

The Painted Bird by Jerzy Kosinski.

Originally published in 1965.

Reviewed by Ed Lengel

The Painted Bird is an allegory about a bird-catcher who reveals his delight in capturing birds, painting them carefully, and then releasing them. As they seek to return to their own kind, the painted birds receive no welcome; instead, they are perceived as intruders and the other birds tear them to pieces. The bird-catcher’s sadism is shocking, but his experiment reveals a fundamental truth about trauma; for its victims, the greatest cruelty is not necessarily the original pain or even its memory; it’s the fundamental and long-standing transformation that damages a person and makes him a “foreigner”—even an object of hatred—among his own kind.

Upon its release in 1965, The Painted Bird was celebrated as an outstanding example of Holocaust literature. The unconventional narrative follows the wanderings of a small boy of Jewish, or perhaps Roma (Gypsy) origin, through the rural villages of Eastern Europe during World War II. His experiences are a litany of horror, dark superstition, and extreme physical and sexual violence—of the worst kind as he becomes a witness to, and participant in, the degradation of humanity to forms worse than bestial. As far as it is a chronicle of historical events, The Painted Bird reveals the terror that Nazism and Soviet Communism unleashed on Eastern Europe during World War II—and it was as such that the novel was originally praised. Though Kosinski intended to show that the darkness was already present in the peasants, Cossacks, and other people he portrays, the war was merely an excuse for releasing it. This is no story—as for example in the 1985 Soviet film Idi I Smotri (Come and See), in which noble partisans are engulfed by Nazi savagery—of purity betrayed; rather, it begins with human debasement and goes on from there.

Kosinski was a Polish Jew who experienced the war as a child and later emigrated to the United States; he laid the footings for his downfall by misrepresenting his struggles. He suggested, inaccurately, that the novel was based on his experiences as an orphaned child set adrift along war’s battle lines; later it was discovered he had spent the war in hiding with his family living under assumed names, and Christian identities. In addition, it was revealed that humble assistants—sworn to silence—had translated his book in English from original Polish manuscripts—undercutting public praise for his “remarkable” English prose. This and other revelations, suggesting that Kosinski was a fraud, that the debasement he presented resided in his own mind rather than in the world at large, severely undercut the book’s “Bird’s” popularity—and—his reputation.

A profoundly enigmatic individual, Kosinski, reveled in the fame that The Painted Bird initially brought him, and traded upon it to move from one success to another. Steps, a sequel published in 1968, earned the National Book Award. The author went on to a series of prestigious ivy-league teaching appointments. Being There, a still-powerful indictment of the hypnotic power of media published in 1971, was made into a highly successful 1979 movie starring the author’s friend, Peter Sellers. By the 1980s, a series of ruthless public exposures about his actual origins, and revelations about the actual process by which he imagined and wrote (or had written) his most famous novel, left Kosinski’s reputation in ruins, and catapulted him into the type of outcast he had originally portrayed.

He committed suicide in 1991.

Only in hindsight have critics come to recognize that Kosinski was not so much a fraud or a salesman, but a deeply fractured person accustomed to living behind a mask. Whatever the source of his tortured—an apt word for describing the scenes he concocted—mind, Kosinski spoke to verities—as he saw them—within human nature. Moving beyond the debased brutality he presented—certainly, a difficult task—clarifies the impact that such brutality had, or has, on human nature; in other words, Kosinski wasn’t writing about humans as perpetrators, but as victims who got entrapped in a never-ending spiral of alienation.

Although the main character in The Painted Bird eventually reunites with his family and even recovers the voice he had lost as a witness to war’s human atrocities, it is hard to see any silver lining in Kosinski’s view of human nature. It’s even plausible that the novel’s marginally happy ending may have been introduced by his editors to relieve the otherwise unremitting bleakness. For all that, The Painted Bird does not deserve the obscurity into which it has lapsed as a result of its author’s personal flaws. They might even serve as a reason for the novel’s reappraisal—and—appreciation.

Ed Lengel is an author, a speaker, and a storyteller.