The Grapes of Wrath

by John Steinbeck

Reviewed by Ed Lengel

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

Originally published in 1939

Taking advice from his wife, Carol, John Steinbeck borrowed the title of his best-selling novel, The Grapes of Wrath, from Julia Ward Howe’s Battle Hymn of the Republic. Dating from 1862 during the Civil War, that song became a triumphant march for the Union Army, beginning with the verses: “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord; He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored.” Steinbeck remarked that, like the hymn, his book was “a kind of march…in our own revolutionary tradition.” As he would have known, however, the “grapes of wrath” was a Biblical reference from the Book of Revelation, 14:19-20, of an angel’s sickle sweeping up grapes from the earth’s vine and throwing them to be crushed in the “great winepress of God’s wrath,” from which blood flowed in torrents.

Steinbeck’s novel speaks to the same scale of human suffering—and injustice. Working in 1936 as a reporter for the San Francisco News, he had chronicled the struggles of migrant workers in California’s fields, orchards, and vineyards. Many of these migrants were desperate farmers and their families—“Okies”—after Oklahoma, representing the once-fertile breadbasket of middle America from which they originated. Like immigrants of the country’s colonial days, and again during the great wave of immigration around the turn of the twentieth century, the migrants fled cruelty and exploitation only to find more of the same in what they had thought would be a land of plenty. Utilizing his first-hand knowledge of their plight and borrowing from others who had written and reported on the same subject, Steinbeck created an epic novel that he hoped would capture the Great Depression’s miseries—and put a tag of shame on the greedy bastards who are responsible.”

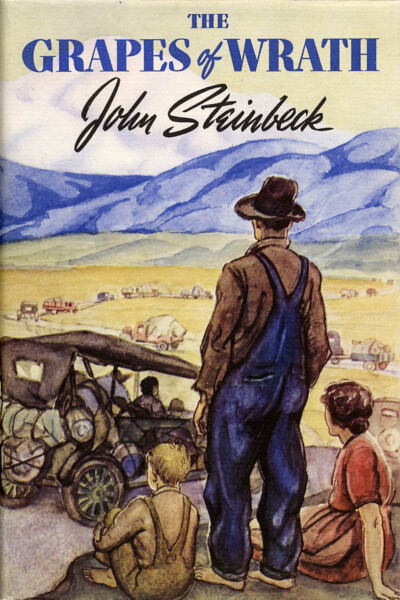

Steinbeck wrote at a breakneck pace, composing an average of 2,000 words a day during the summer and autumn of 1938. Published in the spring of the following year, the pages unfolded the story of the Joad family, led by ex-convict Tom Joad and his sister Rose of Sharon, who along with their friends and neighbors fled the Oklahoma Dustbowl to seek sanctuary in the west. Thrown on their own meager resources after being forced into foreclosure by callous bankers, the Okies journey cross-country via the sun-parched wastelands along Route 66 to southern California, where they joined thousands of other hard-luck cases seeking work in a fertile New Eden.

By the time the novel was published in 1939, most Americans were familiar with iconic photographs of Model T Fords and other elderly jalopies piled high with suitcases and furniture as the Okies carried their possessions in westward caravans reminiscent of refugees in Europe during World War I. But what happened to them after they left? Refusing to let the stage curtain drop, Steinbeck forced his readers to recognize that the refugees found no succor from their fellow men—least of all from the same leaders of business and finance who had, in the eyes of many Americans, been responsible for the Depression in the first place.

The Grapes of Wrath’s villains represented a ruthless and dishonest economic and social system: bankers, businessmen, police, and the lesser people they corrupted into doing their bidding. Although Steinbeck sympathized with President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, he presented well-intentioned government programs and their representatives as being overwhelmed by the scale of human misery, and pathetically unable to relieve the crisis. Organized religion did not offer tangible help, either; Instead, the Joad’s and others had to return to primeval human impulses, unforgettably including nursing at a mother’s breast, to ensure their survival and provide grounds to dream. Tom Joad’s friend Jim Casy, a preacher who has lost his faith in God and Church, transforms his religious impulse, and compassion for others, into a new mission as a labor organizer—and eventually undergoes martyrdom. Justice, Steinbeck clearly implies, will not be achieved without an inevitably violent overthrow of capitalist society.

The Grapes of Wrath was an instant success; more than 400,000 copies were sold within the year; it also got a National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize. John Ford’s 1940 movie version which starred Henry Fonda was toned down, less radical, and successful, but by that time Europe and Asia were deeply embroiled in what we know as the Second World War. The emotional impact of Steinbeck’s book goes a long way in explaining why—until the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941—most Americans chose to stay out of foreign wars. The real conflict, it seemed, had already begun at home.

Ed Lengel is an author, a speaker, and a storyteller.