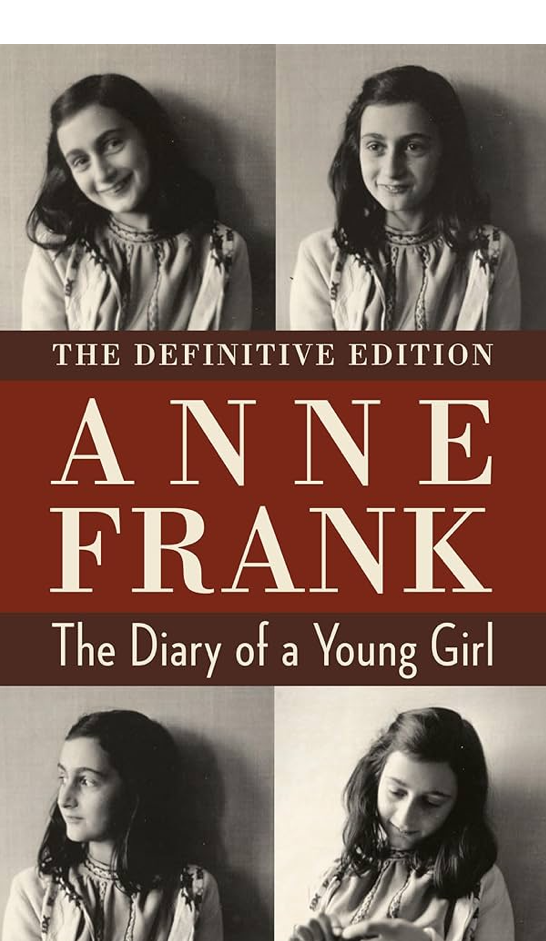

The Diary of a Young Girl

by Anne Frank

The Diary of a Young Girl, by Anne Frank. Edited by Mirjam Pressler. Translated by Susan Massotty. New York: Doubleday, 2001.

Reviewed by Ed Lengel

At the time she wrote her diary, Anne Frank was an ordinary teenager. She was born in Frankfurt am Main, in Germany, on June 12, 1929, into an upper middle-class family. Her parents, Otto Frank, and Edith Holländer, came from wealthy families whose circumstances had been reduced somewhat in the economic turmoil that gripped Germany in the 1920s. Anne, who was bright, stubborn, and rebellious, resented her older sister Margot as a goody two-shoes. Anne liked her father, but looked down on him a little, and felt that he didn’t understand her. Like many teenage girls, she didn’t understand her mother, either.

That the Franks were Jewish didn’t matter much when Anne was born. They weren’t particularly observant. Anne believed in God but adopted a mishmash of Jewish and Christian attitudes toward morality and the afterlife. The only people who cared about their family ancestry, in fact, weren’t Jewish.

Shortly after Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933, Otto Frank—a prescient man—decided to relocate the family to Amsterdam in neighboring Holland. Although they settled in a predominantly Jewish neighborhood, Anne and Margot attended mixed schools, and made friends with Jews and non-Jews. Anne was popular, vivacious, and sharp-tongued—a good friend or formidable adversary among her peers. When the Germans occupied Holland in the spring of 1940, however, everything changed. The girls were forced to attend an exclusively Jewish school, where they were subjected to a series of onerous and humiliating restrictions that reduced them to second-class citizens. Anne never understood why her Jewish heritage should degrade her status in a country she had come to love. But Otto sensed far worse things to come, and he made preparations for sheltering his family.

In the summer of 1942, Otto moved them into a “Secret Annex” in a building where he had operated a small spice manufactory. They shared a number of rooms in the building’s upper levels with fellow Jews Hermann and August van Pels, their teenage son Peter, and eventually a middle-aged Jewish dentist named Friedrich Pfeffer. Otto’s Christian colleagues and friends provided cover for the coterie, sheltering in the annex, and keeping them supplied with food and other necessities insofar as wartime restrictions permitted. Anne realized that she was lucky to be so well off. But she and the annex’s other inmates could never venture outside. Not long after the Franks closed the door—hidden behind a bookshelf—to their annex, German and Dutch Nazis began rounding up Jews for deportation to death camps such as Auschwitz in Poland. Hitler’s “Final Solution” had begun. For the Franks, the only hope of escape would be eventual liberation by the Allies. And in 1942, that was a long way off.

Anne Frank’s diary, which she began shortly before moving to the annex, doesn’t have a whole lot to say about the war, the Nazis, or the outside world, in general. Most of what the Franks knew came from BBC radio broadcasts, gossip brought in from the street by their protectors, and the terrifying sounds of increasingly frequent air raids. Anne didn’t meditate much about being Jewish. Instead, life revolved around daily necessities like food—increasingly poor in quality—cleaning and using the bathroom. Anne and Margot read voraciously and tried to educate themselves in preparation for returning to school when the war was over.

Anne’s mind revolted against this dreary and narrow world. Outside, her life had orbited around human relationships. With only her family and fellow inmates to focus on aside from occasional outside visitors, her thoughts turned savage. As the years went by, she filled her diary with bitter observations about her family and friends, and her resentment for her mother hardened into hatred. At the same time, Anne entered puberty and became more aware of her sexuality; In time, she fell madly in love with Peter. Only, as he slowly began to return her affection did Anne—who had an immense capacity for honest self-reflection—did she realize that her interest in him was mostly manipulative.

Reading Anne Frank’s diary is looking through a window into a young girl’s mind. In time, she and her family become like the reader’s own relations. Editions of the diary published shortly after the war by Anne’s father—the only inhabitant of the annex to survive—were carefully edited to remove graphic references to Anne’s sexuality, and to tone down her criticism of others. The modern, unexpurgated edition brings us much closer to the real Anne Frank—a girl who in many ways was remarkably ordinary, but who dreamed of leaving behind a legacy as a writer, and as such has become immortal.

The Diary of a Young Girl is a powerful learning tool, especially for teenagers. It creates a point of identification–otherwise difficult to achieve in any statistical accounting of the Holocaust’s horrors. The dark, irony of the book is that it simultaneously captures Nazi genocide’s immensity without saying anything about it at all. After having gotten to know Anne and her family so well, the reader runs into a blank wall in August 1944, when the diary abruptly ends. One is left only with silence, surrounded by a terrible awareness that the Gestapo discovered the annex, and that Anne, her mother, Margot, Peter, and all of the others–except Otto–would suffer and die in the camps. This silence is their eternal testament.

Ed Lengel is an author, a speaker, and a storyteller.