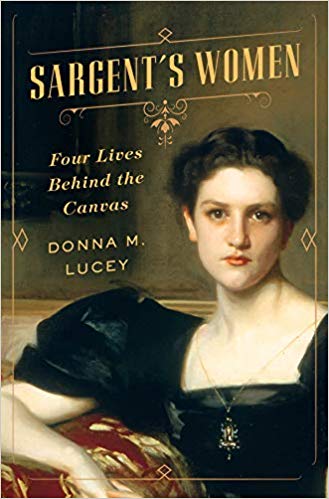

Sargent’s Women: Four Lives Behind the Canvas

by Donna M. Lucey

Sargent’s Women: Four Lives Behind the Canvas

by Donna M. Lucey

336 pp., W.W. Norton, 2017

$29.95

The Gilded Age evokes a host of impressions. On the surface, the era glitters with wealth and beauty: fine clothes, art, grand homes, high living. Its prime characters like J.P. Morgan and John Jacob Astor, appear larger than life; robber barons and self-made plutocrats standing cheek by jowl with blue bloods to form a uniquely American aristocracy. A grimmer reality, we know, lurks beneath the surface. Even the most beautiful families grapple with tragedy and scandal. Below them, millions toil in miserable conditions to escape poverty. Yet these remain all impressions.

Donna M. Lucey adopts a fresh approach to uncovering the humanity that dwells behind the veil of Gilded Age spectacle. Sargent’s Women presents the interwoven lives of four women who sat for, and/or interacted closely with renowned portrait artist John Singer Sargent during the last quarter of the twentieth century: Elsie Palmer, Lucia Fairchild, Elizabeth Chanler, and Isabella Stewart Gardner. Each woman represents a facet of the Gilded Age Anglo-American glitterati, but their personalities are as unique as the portraits that Sargent painted of each.

Elsie Palmer was the daughter of an American railroad baron and an ailing, demanding mother. Like Sargent, she divided her time between England and America—in Elsie’s case, between Glen Eyrie castle outside Colorado Springs, and ancient English country estates. Her portrait, which Sargent painted when she was a teenager, is hauntingly enigmatic, reflecting her personality. Her life story is defined by her search for freedom to make her own choices, out of the shadows cast by her colorful but domineering parents.

Lucia Fairchild was the sister of Sally Fairchild, whom Sargent painted enwrapped mysteriously in a blue veil. Lucey does not find the strong-willed but evidently somewhat irritating Sally particularly interesting, however, and so elects to write about Lucia instead. An artist in her own right, Lucia Fairchild became an accomplished miniaturist who struggled to earn enough money working on commission to support her children and a ne’er-do-well husband. Although she emerged from a prominent–albeit deeply troubled—family and moved among the bright and beautiful (painting for J.P. Morgan, for example), Lucia lived some of her brightest moments as a denizen of the artists’ colony of Cornish, New Hampshire.

Elizabeth Chanler, whose portrait graces the cover of Sargent’s Women, endured an exceptionally painful early life. Connected to the Astors and surrounded by immense wealth, she was orphaned young and sent to an oppressively strict girls’ school on the Isle of Wight. While there she developed a condition that was likely tuberculosis of the hip. Not understanding the nature of the disease, which was incurable at the time, Elizabeth’s doctors—fully supported by her distant and largely unsympathetic extended family—ordered her to be strapped to a board for two years. Despite these ordeals, Elizabeth, whose portrait captures a character marked by fierce determination, breaks free, decisively, to forge her path to happiness.

The final image in the quartet is Isabella Stewart Gardner. Painted (unlike the other three) when the subject was already in middle age, Sargent’s portrait reveals a woman who had already blazed her own trail. Born in 1840 and married into a blue-blood Boston family that snubbed her socially, Isabella elected from an early age to disdain convention. Indeed, she gleefully shocked her peers whenever possible, with her indulgent husband’s tacit acceptance. Never short of cash, she traveled all over the world and became a renowned art collector, founding a magnificent museum that still stands in Boston.

Taken as a whole, Sargent’s Women is a fine, and all-too-rare example of humanistic history. Lucey writes—as a good portraitist paints—with empathy. Her four women are not subjects, but people, glowing with inner energy. Not all are equally compelling. Isabella Stewart Gardner is perhaps the least interesting, for her portrait evokes little sense of inner struggle. Instead, her biography presents a triumphant chronicle of exotic travel (well-attended by servants) and artistic empire-building. The other three women, by contrast, are fascinating and entirely sympathetic despite their human imperfections.

Lucey’s bases her narrative on wonderfully evocative letters and diaries, but her restless prose alternately impresses and infuriates. She hurries from event to event, and from person to person, with an often breathless impatience that perhaps reflects the dazzle of the Gilded Age. On occasion, however, the reader is tempted to ask her to stop and explain discrepancies. How, for example, is it that Lucia Fairchild “doesn’t have two cents to rub together” in one paragraph, and is constructing a magnificent Italianate villa the next? This stylistic imperfection aside, Sargent’s Women is an intriguing, eminently readable book that restores humanity to the Gilded Age without tarnishing its luster.

Ed Lengel is an author, a speaker, and a storyteller.