Rachel Carson: Not So Silent

Special to the Newsletter

by Michael F. Bishop

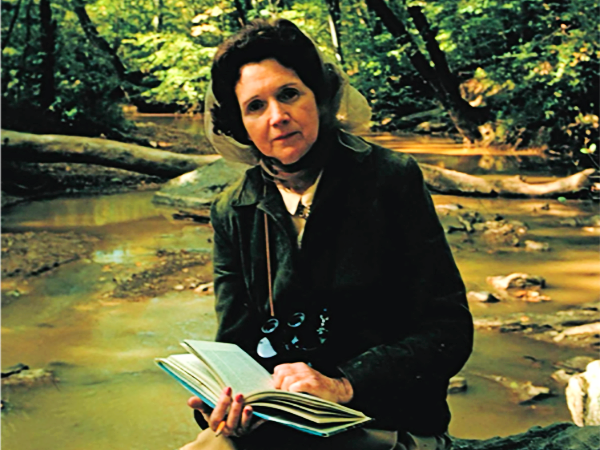

Rachel Carson was not one for understatement. In Silent Spring, published in 1962 and the most famous of her works, she issued a stark warning: “The most alarming of all man’s assaults upon the environment is the contamination of air, earth, rivers, and sea with dangerous and even lethal materials.”

She was born in 1907 on the Allegheny River in western Pennsylvania, and the waterways of the world would long be her life’s passion. Her father was an insurance salesman and the family lived in comfort on a large farm that Rachel loved to explore. A brilliant student and natural writer, she became a published author at the age of ten. After going to college near the family home, she attended graduate school at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, by which time her passion for biology and zoology was clear.

Only her family’s deteriorating financial state deterred her from pursuing a doctorate, but armed with a master’s degree she became a writer at the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries. Her writings about oceans led to a blossoming journalistic career that included the well-received book, Under the Sea-and–The Sea Around Us,–a huge bestseller–which made her famous.

Rachel Carson loved the oceans and derived tremendous joy from the natural world. Her writings were both informed and celebratory. But she became a prophet of doom, warning her readers about the threat of pesticides to the sea and air. She observed, “It is not my contention that chemical insecticides must never be used. I do contend that we have put poisonous and biologically potent chemicals indiscriminately into the hands of persons largely or wholly ignorant of their potentials for harm.”

This warning was at the heart of Silent Spring, which-more than six decades since its publication–has become a kind of biblical text for the environmental movement. It was years in the making, and the result of detailed research and careful composition. As the book neared publication, Carson was diagnosed with breast cancer, which made the latter stages of its composition an ordeal. The book was an immediate bestseller and was serialized in The New Yorker. It has sold more than two million copies.

The chemical industry reacted with fury, disputing Carson’s findings and portraying her as an alarmist. But the domestic sale of DDT was banned a decade after the book was published. How much of that can be credited to Carson is still unclear, but what is beyond dispute is that Silent Spring launched a new phase in the environmental movement, and it remains the most influential ecological study in history.

For Carson, the cause of the environment was an ongoing struggle:

For we all are united in a common cause. It is a proud cause, which we may serve secure in the knowledge that the earth will be better for our efforts. It is a cause that has no end: there is no point at which we shall say, ‘Our work is finished. ‘ We build on the achievements of those who have gone before us; let us, in turn, build strong foundations for those who will take up the work when we must lay it down.

But for her, the fight would end too soon. The grueling radiation treatments for her cancer left her weak. The cancer spread, and she developed other illnesses. Carson died on April 14, 1964, at the age of 56. Some of her ashes were buried in Rockville, Maryland, outside of Washington, D.C., and some were scattered off the coast of Maine, a place she loved.

Her name would live on. Schools from coast to coast are named for her. President Jimmy Carter awarded Carson a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1980, and her likeness would later appear on a United States postage stamp. The biologist E.O. Wilson would write in 2002, “Forty years ago, Silent Spring delivered a galvanic jolt to public consciousness and, as a result, infused the environmental movement with new substance and meaning.”

Even after her death, her writing continued to inspire lovers of nature. The posthumously published The Sense of Wonder vividly conveyed the joy she derived from the natural world:

Those who dwell, as scientists or laymen, among the beauties and mysteries of the earth are never alone or weary of life. Whatever the vexations or concerns of their personal lives, their thoughts can find paths that lead to inner contentment and to renewed excitement in living. Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts.

Michael F. Bishop, a writer and historian, is the former executive director of the International Churchill Society and the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission.