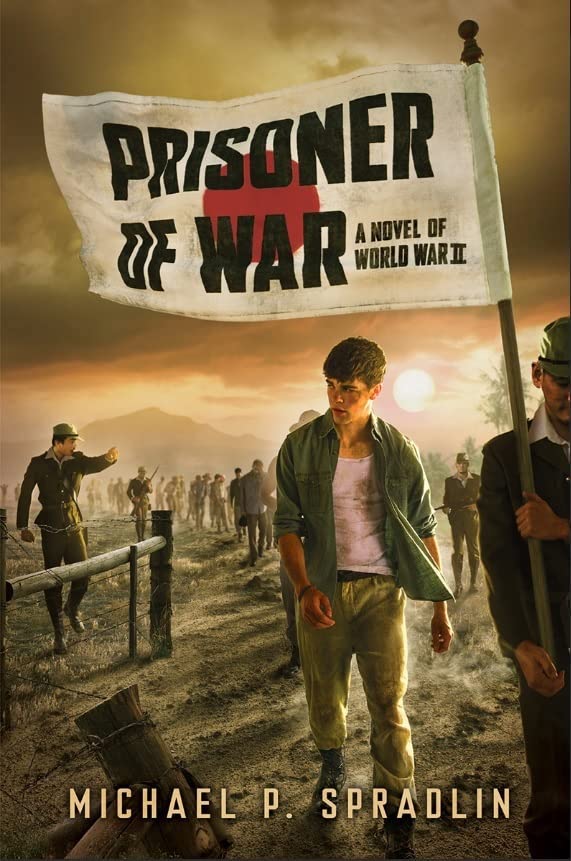

“Prisoner of War: A Novel of World War II”

by Michael P. Spradlin

Prisoner of War: A Novel of World War II

by Michael P. Spradlin

272 pp., New York: Scholastic Press, 2017.

Reviewed by Ed Lengel

Violence has always been a challenging theme for authors of young adult literature. Although writers have become increasingly willing in recent years to address issues like domestic violence, institutionalized violence—warfare—seems to unsettle even the boldest of them. Or perhaps it might be safer to say that warfare intimidates editors at the major publishing houses, who suppose that engaging with the subject head-on, rather than obliquely, might seem like an endorsement.

And yet warfare has never been more relevant in American society than it is today. Many thousands of young adults currently struggle to engage with family members returned from military service, and sometimes combat, in places like Iraq and Afghanistan. Psychologists are only just beginning to study and understand secondary trauma—the process by which those who experience trauma firsthand–such as veterans–can transmit that trauma to family members, and even to grandchildren; only one way in which institutionalized violence can lead to domestic violence. But it goes both ways.

If young adult writers and editors are fearful of addressing institutionalized violence in the contemporary world, then they might more easily approach the topic at one step removed, through historical fiction. One such example is Michael Spradlin’s Prisoner of War: A Novel of World War II. The author has written several action-adventure novels for youths—a number of which are set in World War II– tells the story of a young Henry Forrest who joins the U.S. Marines, fights in the Pacific Theater, and then endures the trials of life in a prisoner of war camp.

Violence is Spradlin’s theme right from the outset. The novel begins with Henry reminiscing about his troubled youth. His mother was killed in an accident when he was seven. Afterwards, Henry’s father becomes verbally and physically abusive, beating his son, repeatedly. In an era when domestic abuse generally went unrecognized and untreated, Henry’s only route of escape is to run away from home and, as a fifteen-year-old, lie about his age to join the Marine Corps.

So, while Pearl Harbor is attacked by the Japanese on December 7, 1941, Henry is serving at an American base in the Philippines, that ambushed the same day (December 8, locally). Spradlin describes the fighting that follows realistically, with doses of brutality and excitement, all the way to its historical conclusion as the Marines and other American and Filipino forces surrendered to the Japanese at Bataan in April 1942. Afterwards, Henry and his fellow Marines endure sickening brutality at the hands of their Japanese captors in what came to be called the Bataan Death March. Once again, Henry Forrest is subjected to violence of the powerful against the powerless, just as he had known in childhood–only much worse.

As Henry learns in the months that follow and struggles to survive alongside his friends Jamison and Gunny, old clichés taught by American society, and wartime propaganda, are no longer believable. In the movies, a victim who gathers the courage to stand up to a schoolyard bully, and punches him in the nose, wins self-respect and peer approval and exposes his cringing enemy as a coward. That’s the “lesson” taught by Bing Crosby’s character, Father “Chuck” O’Malley, to the children under his care in the 1945 smash hit The Bells of St Mary’s. The obvious parallel is to America standing up to the Axis bullies of Japan and Germany and giving them their just deserts. Reality, though, doesn’t work that way, as Harry discovers. With Father O’Malley nowhere to be found in the prisoner of war camps, any American who tries to stand up to his Japanese captors is liable to be bayoneted or beaten on the spot—a predicament reflecting the realities of Henry’s childhood as a victim of child abuse.

The allegories between warfare and domestic abuse are drawn gently in Prisoner of War, but unmistakable for all that. The principles of survival, as Henry finds out, apply in both situations. Endurance. Courage. Silent defiance. Solidarity with fellow sufferers, as Henry’s circle of friends grows to include doughty Australian captives. Perhaps most of all, victims demonstrate a stubborn determination to abandon higher principles, refusing to submit—unlike their Japanese captors—to becoming internally brutalized.

Throughout Prisoner of War, the author evades clichés, simple answers, and Hollywood endings. Along with its overall historical accuracy and the believability of its characters, that refusal to delude readers with false resolutions stands among the book’s greatest strengths. At the end, though, the reader does come full circle from Henry’s origins to his wartime experiences, as he recognizes the reality and permanence of all that he has lost, but also manages to stare down and finally vanquish the demon of violence that has followed him through life. Prisoner of War is a model of how historical fiction can be profoundly relevant to today’s challenges.

Ed Lengel is the Chief Historian at the National Medal of Honor Museum; Arlington, Texas