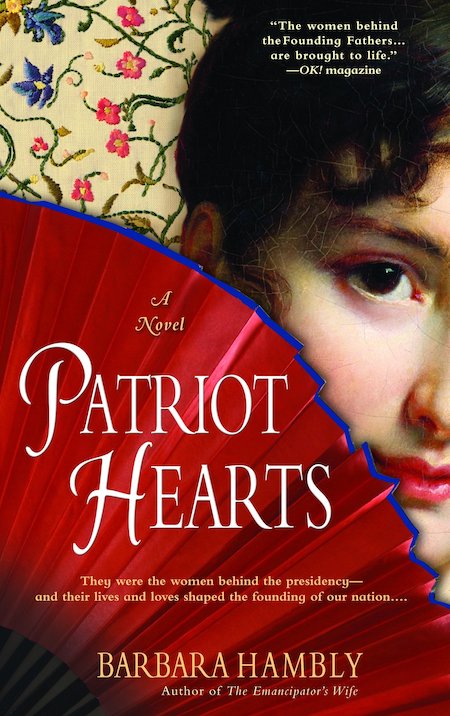

“Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers”

by Barbara Hambly

Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers

by Barbara Hambly

448 pp., New York: Bantam Dell, 2007

$14.00 paperback reprint

Women have only just received credit as significant contributors to the founding of the United States. History books, novels and other literature written over the two centuries after 1776 typically either ignored them altogether or presented them as appendages or objects of curiosity. Stories of Revolutionary War battles, for example, are replete with legends of fascinating local beauties who beguiled and distracted–or nobly defied–British officers. Otherwise, their duties appeared limited to staying at home to mind the children and cook the meals while their menfolk were away fighting and determining the course of history.

This neglect also applied to the wives and other female helpmates of the Founding Fathers. Their images in the literary canon–insofar as they developed at all–were unflattering. Martha Washington: mild, insignificant and a bit soft-headed, lurked meekly in the shadows behind her illustrious husband. Abigail Adams: vaguely associated with an early interest in women’s rights, put any independence of mind aside as she became a loyal cipher to the redoubtable John Adams. Some vestiges of Dolley Madison’s formidable personality also lingered after her 1849 death, but she, too, was depicted more as a quirky woman who saved George Washington’s White House portrait from British marauders, than as a force on her own. As for the women in Thomas Jefferson’s life: his wife, Martha, who died in 1782, was little more than a portrait on a wall; enslaved African American Sally Hemings remained almost entirely invisible—little more than a name whispered in tones of scandal—until the late twentieth century.

Barbara Hambly’s Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers, was published in 2007, at a time when historians and other writers were only just beginning to turn their attention to the women of the founding era—not just as auxiliaries to male leaders, but as free-minded and free-acting individuals who played major roles in shaping the nation. Four women: Martha Washington, Abigail Adams, Dolley Madison, and Sally Hemings, appear from different chronological vantage points: 1787, 1793, and 1800; with Dolley looking back on it all from the perspective of Washington, D.C., in 1814.

Martha Washington copes with the challenges of managing a vast estate in the absence of her husband, endlessly drawn to national affairs. She worries over her troublesome grandchildren—the last of her own four children having died in 1781—and maintains an uneasy outlook on the enslaved men and women who participate closely in her daily activities. Above all, though, she is a loyal supporter—and lifter–of her husband’s political career, with a keen and intelligent awareness of the American political milieu.

Abigail Adams, far from having abandoned the independent thinking of her youth, maintains a close interest in national politics and international affairs. These she not only observes, but helps to shape, by counseling her husband and friends. At the same time, she is a devoted mother and mentor to her children, one of whom becomes another president of the United States.

Meanwhile, Sally Hemings struggles, constantly, to navigate the borderlands between her identity, enslavement, and her relationship with a white slaveholder who happens to be her brother-in-law–and one of the most powerful men in the young United States. Her children with Thomas Jefferson inspire her love and sense of obligation, but their identity is also unclear. Never to be accepted in the white world, she faces rejection from her peers, and her fellow enslaved African Americans. But, through all of this, she too, gains a perspective on national affairs.

Finally, Dolley Madison, experiences many of the challenges that partially hampered the other three, by virtue of her marriage to James Madison. She raises children in a new world, and witnesses the dangerous political divisions arising from the rivalry between Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton. But she also muses upon them from the perspective of 1814, when America was once again at war with Great Britain and struggling for survival. Thoughtful and wise, she provides overarching perspective to place individual experiences in context and give them meaning. And she serves as a bridge to the future by virtue of her long life—just enough to see the signs of a coming Civil War.

Founding Mothers is every bit as formidable as the women who inspired it. Far from being a frothy bit of light literature, it gives life—admittedly much of it hypothetical—to four women who until recently had dwelt in the shadows of American history. Hambly undertakes a difficult task, but she does not always succeed in attempting to build a unified narrative structure around four women whose lives, while concurrent, did not often intersect. Changing perspectives and flashbacks sometimes make the story difficult to follow. On a deeper level, though, Hambly reveals the critical roles that women on all levels played in the founding and troubled growth of the United States. Although they usually worked behind the scenes, their communications and activities assembled the framework upon which the country—and society—were formed.

Edward G. Lengel is Senior Director of Programs for the National World War II Museum’s Institute for the Study of War and Democracy in New Orleans, Louisiana.