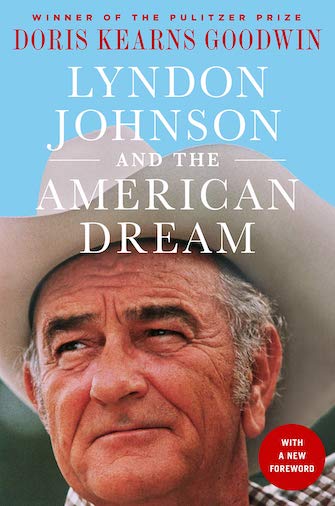

“Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream”

by Doris Kearns Goodwin

Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream

by Doris Kearns Goodwin

432 pp., New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1976

Reprint edition, 2015

Paperback $14.89

Five days after John F. Kennedy’s assassination, his successor, Lyndon Baines Johnson, delivered a national address, which included Congress and the justices of the Supreme Court.

When he was partially through the speech, the new president said, “Let us put an end to the teaching and the preaching of hate and evil and violence. Let us turn away from the fanatics of the far left and the far right, from the apostles of bitterness and bigotry, from those defiant of law and those who pour venom into our nation’s bloodstream.” The words were meaningful, because many Americans felt wounded and afraid; they longed for peace and rebuilding.

Less than a year later, Johnson, still sounding the clarion call to combat extremism, won by a landslide in the 1964 presidential election. The Democrats who controlled Congress were eager to embrace Johnson’s ambitious legislative agenda, and the president—confident with his mandate—leaped into securing the passage of a series of ambitious programs to be known as the Great Society. Johnson’s objective was to rub out poverty.

Johnson did not know he would fall so far.

By the start of 1968, the administration was in chaos. Young people were rioting; American cities were in flames, and hundreds of people were killed. The Great Society had gotten mired in bureaucratic inertia and ineptitude, and the economy was falling fast into a spiral of runaway inflation. Worst of all, the country had been sucked into the endless Vietnam War. Half a million American troops were on the ground in the Asian jungle-–with more on the way. And, protestors swarmed the streets, and chanted at the White House gates, “Hey, Hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” Heartbroken, Johnson declined to seek reelection.

He would be dead within five years.

This epic tragedy is the subject of Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream. Now, one of the nation’s greatest historical biographers, Goodwin started this book just out of graduate school, while working as an aide to Johnson during the last months of his presidency, and as an assistant on his intended–but never completed–autobiography. Much of it is based on interviews she conducted with him for that purpose, but often, she ended up listening to his angry, bitter ramblings.

Originally published in 1976, when memories of the Johnson presidency were still fresh for most Americans, Goodwin’s “Lyndon Johnson” is now–in some ways–neither fish nor fowl; neither history nor biography. Instead, it reveals an extended investigation into Johnson’s personality, followed by an analysis of the salient points of his presidency, with a view determining how he governed, what went wrong, and why. Readers are assumed to already have a deep understanding of the primary facts and chronology of those Johnson years, but they ended fifty years ago.

This assumption—reasonable in 1976, but not so in 2020—is one of the weaknesses of the book for modern readers. Another, more significant problem is Goodwin’s now badly dated use of Freudian theory and terminology to psychoanalyze her subject–theorizing, for example–about how Johnson’s inner conflicts with his mother haunted his conduct as an adult. This– despite the odd irony– that Goodwin writes almost nothing about Johnson’s relationships with Lady Bird and his daughters.

When Goodwin proceeds to analyze the Johnson presidency, it glows with the brilliance that presages the greatness of her later works. Dissecting Johnson’s magnificent interpersonal, negotiating, and managerial abilities that were apparent during his days as Senate Majority Leader, Goodwin reveals how his talent, overwhelming need for admiration, power and control—turned on him and sabotaged his conduct as a president. Focused—at first—on the Great Society, which Johnson regarded as his personal gift to the nation, he shifted his attention to Vietnam war—and arrogantly presumed—that he and the nation—could juggle Social Change—and slaughter, together.

Worse, the style that had served him so well in the Senate–and to some degree as president– manufacturing consensus in the course of often contradictory promises, personal deals and threats, translated poorly to Johnson’s relationship with the media and the American people. Johnson’s obsessive secrecy, manipulation, and intentional misdirection came across as outright deception—which in fact it was, especially with respect to Vietnam. Over time, as Goodwin shows, Johnson’s frustrations led him to narcissism; he surrounded himself with sycophants; later, Johnson believed he was enclosed by conspirators; afraid to acknowledge his mistakes.

Many Americans view the Johnson presidency as a period of missed opportunities. Goodwin, while acknowledging her subject’s good intentions, does not go quite that far. Rather, she suggests, the beginnings of Johnson’s downfall were in the successes of his greatest achievements in–for example–Civil Rights in 1963-1964. Observed from any angle, the story of Lyndon Baines Johnson presents a cautionary tale during a time of renewed national division.

Edward G. Lengel is Senior Director of Programs for the National World War II Museum’s Institute for the Study of War and Democracy in New Orleans, Louisiana.