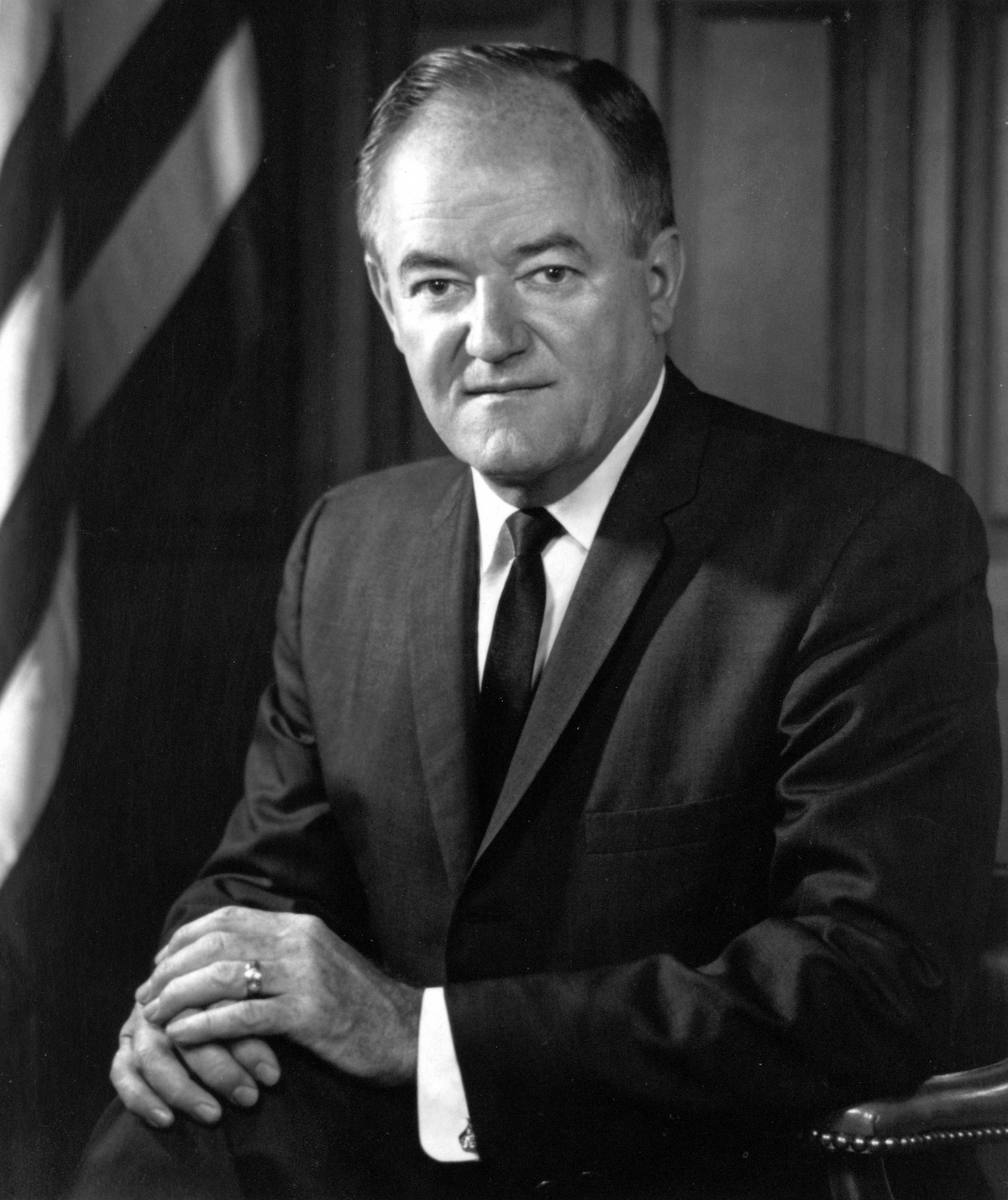

Hubert Humphrey: Happy Warrior

Special to the Newsletter

by Michael F. Bishop

On August 14, 1980, President Jimmy Carter formally accepted the nomination of the Democratic Party for a second term in the White House. In his speech before thousands of delegates packed into Madison Square Garden in New York, Carter paid tribute to the 38th vice-president of the United States, Hubert H. Humphrey, in words that were complimentary and slightly embarrassing:

And we’re the party of a great leader of compassion—Lyndon Baines Johnson, and the party of a great man who should have been President, who would have been one of the greatest Presidents in history—Hubert Horatio Hornblower—Humphrey. I have appreciated what this convention has said about Senator Humphrey, a great man who epitomized the spirit of the Democratic Party.

Carter’s slip of the tongue, in which he confused the former vice-president’s name with the hero of C.S. Forester’s naval adventures, inadvertently captures the mixed legacy of Hubert Humphrey, a liberal icon who commanded affection and respect, but whose career was often marked by embarrassment and defeat.

Hubert Horatio Humphrey, Jr., was born in the town of Wallace, South Dakota on May 27, 1911, to a pharmacist/politician and his Norwegian immigrant wife. Ambitious and intelligent, Humphrey was determined to become a professor, but the family’s financial reverses forced him to become a pharmacist instead.

But this turned out to be a temporary detour; eventually he graduated from the University of Minnesota and Louisiana State University. He returned to the former to complete a doctorate, but the lure of politics was too great. After a brief teaching career, Humphrey ran for mayor of Minneapolis and won in 1945—on his second try. He was an activist leader devoted to the cause of civil rights, and easily won reelection.

He became a leading light in Minnesota politics, and supporter of President Harry Truman, who faced a daunting challenge for the 1948 Democratic nomination against the segregationist “Dixiecrat” Senator Strom Thurmond. Truman prevailed and went on to defeat Republican nominee Thomas Dewey in one of the most unexpected results in American political history. Humphrey was elected to the Senate in the same year. Soon, he emerged as the acknowledged leader among the liberals; he was re-elected twice but lost his pursuit of the presidential nomination three times.

Humphrey was dubbed “The Happy Warrior” because of his ebullient personality and refusal to bear a grudge. He could also be quite funny, having once quipped: “To err is human. To blame someone else is politics.” He was a leading champion of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and a trusted ally of President Lyndon B. Johnson, who had been elevated to the White House the year before upon the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in November 1963. This left a vice-presidential vacancy that would remain until the next election, as there was not yet a constitutional means of appointing a vice president. Johnson picked Humphrey as his running mate in 1964; together they defeated Senator Barry Goldwater, the Republican nominee, in a landslide.

Humphrey was an exceptionally loyal vice president, even as he observed Johnson’s increasing commitment to war in Vietnam with unease. After Johnson’s shocking announcement that he would not run for reelection in 1968, Humphrey entered the race for the Democratic nomination but faced challenges from antiwar candidates Senators Robert F. Kennedy and Eugene McCarthy. Kennedy was assassinated in June and Humphrey won the nomination but lost—in a close election—to the Republican nominee/former vice president Richard M. Nixon.

It was ironic that the political burden of a brutal and unpopular war should have fallen on the idealistic Humphrey during the 1968 election. He once observed, “The pursuit of peace resembles the building of a great cathedral. It is the work of a generation. In concept it requires a master-architect; in execution, the labors of many.” But he remained a loyal Johnsonian lieutenant even in the face of mounting casualties in Vietnam and bitter protest at home. His critics would suggest that whenever his ambition conflicted with his ideals, his ambition prevailed.

Humphrey returned to teaching, but the political bug would bite again, and in 1970 he returned to the Senate. His presidential ambition still consumed him, and he ran for the Democratic nomination in 1972, losing to his Senate colleague, George McGovern. A Senator to the last, he died of bladder cancer on January 13, 1978.

After his death Humphrey achieved the acclaim that had so often been denied him in life. He received the Congressional Gold Medal, and the Medal of Freedom—the latter from Jimmy Carter—who had mangled his name during the 1980 convention.

Humphrey was buried in Minneapolis under a gravestone that reads, “I have enjoyed my life, its disappointments outweighed by its pleasures. I have loved my country in a way that some people consider sentimental and out of style. I still do, and I remain an optimist, with joy, without apology, about this country and about the American experiment in democracy.”

Michael F. Bishop, a writer and historian, is the former executive director of the International Churchill Society and the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission.