“The Proposition is Peace”

Edmund Burke and America

Special to the Newsletter

by Michael F. Bishop

Many of the leading lights of the American Revolutionary generation were masters of the English language and lent their talents to their country’s cause. Thomas Jefferson was an exceptional prose stylist, Patrick Henry a fiery orator, and Alexander Hamilton and James Madison were brilliant explicators of the young republic’s constitution.

But one of the most eloquent and unlikely champions of the rights of the American colonists was an Irish member of the British Parliament. For nearly three decades, from 1766 to 1794, the Palace of Westminster echoed with the passionate speeches of Edmund Burke, whose devotion to the British Empire was combined with a withering critique of its failings in America, India, and Ireland. The poet William Butler Yeats would later immortalize Burke’s quest for justice for these imperial possessions as a “great melody”. In the years leading up to the American Revolution, Burke warned his countrymen that the government’s occasionally heavy-handed imperial policies were violations of the colonists’ rights as Englishmen and likely to lead to disaster. In this—as in so many other things—he was to be proven right.

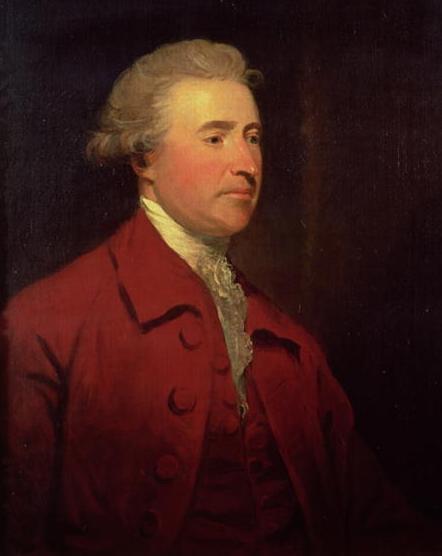

Edmund Burke by James Northcote

Edmund Burke was born in Dublin in 1729, the son of a successful Protestant solicitor and his Catholic wife. He was educated at Trinity College and moved to London at the age of twenty, to fulfill his father’s wish that he too would study law. But the subject had no charm for him, and Burke soon devoted his considerable literary gifts to what he considered more elevated subjects. He authored such tracts as A Vindication of Natural Society, a sophisticated satire about [Henry St. John] Bolingbroke, [politician, philosopher], and A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. It seemed that the young man from Ireland–with an accent “as strong as if he had never quitted the banks of the Shannon” –had the makings of a sage.

But the government soon beckoned. In 1765 he was appointed private secretary to the new prime minister, the Duke of Rockingham, and the following year was elected to Parliament. His public engagement with America began with his maiden speech that year, in which he called for the repeal of the Stamp Act, which levied duties on legal documents in the colonies. His rhetorical brilliance soon made him famous, and he would for many more years urge a more enlightened colonial policy in America.

Not long before Lexington and Concord, Burke beseeched his parliamentary colleagues, “seek peace and ensue it; leave America, if she has taxable matter in her, to tax herself…Be content to bind America by laws of trade; you have always done it…Do not burthen them with taxes…No body of men will be argued into slavery.” Months later he would declare that the “people of the colonies are descendants of Englishmen…They are therefore not only devoted to liberty, but to liberty according to English ideas and on English principles.” He deplored the prospect of war, knowing that it would cause untold suffering and convinced that it would inevitably lead to the loss of colonies anyway. He said to his colleagues, “The proposition is peace. Not peace through the medium of war, not peace to be hunted through the labyrinth of intricate and endless negotiations, not peace to arise out of universal discord…simple peace, sought in its natural course and in its ordinary haunts. It is peace sought in the spirit of peace and laid in principles purely pacific.” And yet the war came.

But for all his sympathy with the American colonists, he could not endorse their revolution. Burke, who would come to be recognized as the founder of modern conservatism, articulated a humane vision of ordered liberty that treasured ancient institutions and recognized the fragility of civilization. To Burke, society was “a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.” To Burke, who believed in incremental change, revolution—whatever its motives and justifications—was always suspect.

And thus, the French Revolution, which began in 1789 and was passionately supported by many of Burke’s fellow Whigs; by Jefferson, and his political followers in America, horrified him. He perceived its radical character and set himself against it from the start, warning in his most famous work, Reflections on the Revolution in France–published in 1790–that the revolutionary fervor on the streets of Paris was like a “wild gas”. He warned that it would soon lead to bloodshed and the eventual emergence of a military strongman. Robespierre’s guillotine and the rise of Napoleon would prove Burke right again.

Supporters of the French Revolution in Europe and America were shocked by what they saw as Burke’s betrayal of his lifelong fight against oppression. Jefferson acidly condemned “the rottenness of his mind” and his “wicked motives.” But it was Burke who accurately foresaw the violence and upheaval of the Revolution and its aftermath. Whereas the Americans had been prepared to fight for their natural rights as Englishmen, the French envisioned a more fundamental reordering of society. He warned, “Rage and frenzy will pull down more in half an hour, than prudence, deliberation, and foresight can build up in a hundred years.”

Burke’s volcanic passions sometimes made him a poor politician, and he never held one of the high offices of state. Indeed, his friend and fellow Trinity graduate, the poet Oliver Goldsmith, lamented that Burke,

“…born for the universe, narrowed his mind,

And to party gave up what was meant for mankind;

Though fraught with all learning, yet straining his throat

To persuade Tommy Townshend to lend him a vote…”

But another of Burke’s friends, Dr. Samuel Johnson, one of the giants of eighteenth-century letters, was closer to the heart of the matter: “You could not stand five minutes with that man beneath a shed while it rained, but you must be convinced you had been standing with the greatest man you had ever yet seen.”

Burke died in 1797.

Michael F. Bishop, a writer and historian, is the former executive director of the International Churchill Society and the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission.

Editor’s Note: This piece is reprinted from its original run in September 2023.