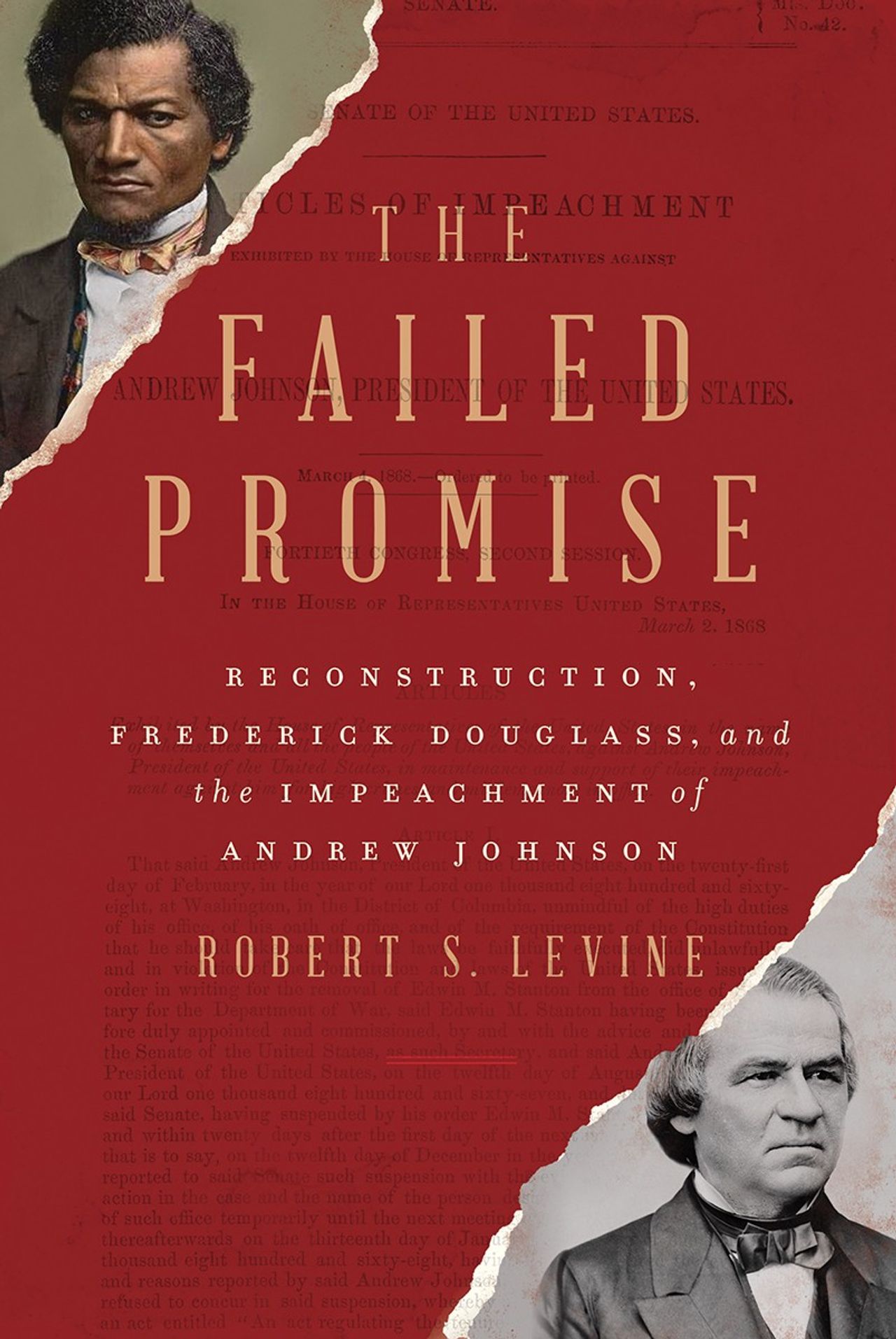

“The Failed Promise” by Robert S. Levine

The Failed Promise: Reconstruction, Frederick Douglass, and the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

By Robert S. Levine

Norton, 332 pages

If the Civil War is often thought of as America’s “Iliad,” the period immediately following it more resembles “King Lear”: the woeful, bombastic tale of a flawed leader whose vanity eclipsed his better instincts.

When Andrew Johnson—“King Andy” to his detractors—assumed the presidency in early 1865, many Republican politicians considered him the best possible person to oversee Reconstruction. Although he was a Democrat and the son of a tailor who went through life with an outsize chip on his shoulder, Johnson had earlier caught the nation’s attention by taking a heroic stand against secession in Tennessee. As the wartime governor of that state, he unilaterally (and illegally) freed the state’s enslaved people. Then, in a remarkable and widely publicized speech in October 1864, he declared himself the “Moses of the Colored Men,” a man prepared to lead the formerly enslaved population of the South to freedom.

Within six months, the same progressive leaders who praised Johnson not only had soured on him, they had begun to consider impeaching him. Outside Congress, no one expressed greater hope and disappointment in the administration than Frederick Douglass, the most influential African-American writer, speaker, and thinker of his era, who initially tried to steer the president toward black suffrage and then, in frustration, became one of the earliest critics to call for his removal from office.

In “The Failed Promise,” Robert S. Levine has written an engrossing account of these two men and the fractious period that began after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox and the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. His book presents the battle over Reconstruction primarily from the perspectives of Johnson and Douglass, in the process illuminating what was at stake in the febrile political climate of the postwar period.

We tend to forget that the United States was born twice. Its first nativity is celebrated on the Fourth of July. The second followed a bloody four-year war in which nearly three-quarters of a million soldiers died. In the wake of the conflict, the country found itself at a crossroads, confronted once again with the task of imagining a new future for itself. Under what conditions should the rebellious Southern states be re-admitted into the Union? How were the rights and safety of a newly free population to be secured? Was it possible to achieve both of these goals at the same time? If not, which one should take precedence?

In the language of the day, the battle hinged on Reconstruction versus restoration—the latter term emphasizing reunification with the South, the former legal protection for black people. Mr. Levine’s special contribution to this history is to emphasize the role Douglass and a host of other African-American writers and thinkers played as advocates for Reconstruction. Using a wide range of black newspapers and letters, he shows Douglass tirelessly advocating for black suffrage, which he came to consider as important to the future of America after the war as emancipation had been before. In Douglass’s analysis, political participation was the only durable safeguard black people had against the virulent racism that continued long after slavery was abolished.

It quickly became apparent that the “Moses of the Colored Men” did not agree. Johnson, a Southerner who resented the lofty manners of plantation aristocrats, nevertheless considered the re-incorporation of the Southern states crucial to the future of the U.S. He also believed it was the prerogative of the president—not of Congress—to determine how this should occur. In his first year in office, he provided amnesty for rebel leaders, agreed to allow former Confederates to hold political office and, in what Douglass and the Republican congress felt were especially bitter betrayals, opposed both the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed birthright citizenship. (The opposition was ignored by Congress and the Amendment was ratified, anyway.)

When racial violence erupted in New Orleans and Memphis, Douglass and other African-American leaders claimed that Johnson had been responsible for the resulting deaths. “The Failed Promise” includes in its appendix one of Douglass’s most fiery and effective speeches from the era, “Sources of Danger to the Republic,” which warns against the extension of executive privilege and identifies universal suffrage (including female suffrage) as the best long-term preventive against tyranny.

One of the most gripping episodes in this book is an encounter between Johnson and a group of black advocates that included Douglass. Johnson brought a stenographer to the White House to record the meeting, expecting the conversation to reveal the high regard in which he was held by black people. Instead, the transcript, which was released to newspapers throughout the country, displayed Douglass’s canny arguments in favor of equal rights for black people. It also exposed Johnson’s temporizing refusal to commit to this goal.

It was this unwillingness that, ultimately, moved Republican leaders to impeach Johnson (the actual charges were minor technicalities). Mr. Levine ably narrates the proceedings, which began in February 1868 and which ultimately resulted in no conviction. His term almost over, Johnson became a lame duck with no appreciable influence on Republican Reconstruction. Still, by the end of his term, the Southern states had been re-admitted to the Union and numerous “black codes” had been put into place by white Southerners who wished to curtail the rights and freedoms of the formerly enslaved. The “failed promise” of Mr. Levine’s book refers not only to Johnson’s disastrous presidency but more generally to Reconstruction, which lasted little more than a decade. If, as Mr. Levine writes, Lincoln’s successor “turned out to be the absolutely wrong president for his times,” his vision of postwar America largely prevailed.

While the author expertly depicts Douglass—he has written about the great orator before—his portrait of Andrew Johnson stands out. In this book, Johnson is a vexing, divided and, for these reasons, ultimately intriguing person. Deeply insecure, craving approval (part of the reason he described himself as a “Moses” figure whenever he spoke to black people), Johnson also lashed out intemperately at his critics. A man with a penchant for making off-the-cuff speeches, some of which were almost certainly fueled by overindulgence in alcohol, he could variously show great kindness to black people and reveal superb political instincts. (At one point in his presidency, Johnson considered offering Douglass a leadership role in the Freedmen’s Bureau, a move that would have tempered the black leader’s critique of the administration. Douglass wisely decided against accepting.)

Mr. Levine is careful not to place the blame for the botched Reconstruction entirely at the 17th president’s feet. And in these pages he makes the same point that Douglass did 150 years earlier—that the northern representatives, while insisting that southern states enfranchise black citizens as a condition for returning to the Union, made no such demands upon their own states.

Mr. Levine poignantly captures a moment when the future of the United States was up for grabs, when it was possible to imagine the full political participation of blacks and whites across the nation. In so doing, the author suggests the tragic consequences of failure and the way in which those consequences are still very much with us.

Mr. Fuller is Herman Melville Distinguished Professor of American Literature at the University of Kansas.