Should the British Have Won the Revolutionary War? Monticello’s VP Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy Explains That — and More!

The British conquered every American city at some stage of the Revolutionary War. So why did they lose the American Colonies to the patriots?

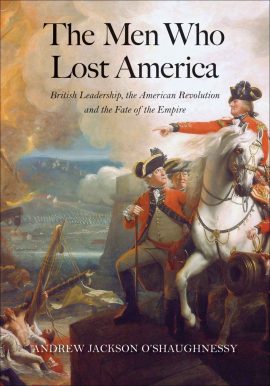

In his award-winning book, “The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution, and the Fate of the Empire,” author and historian Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy reinterprets this fascinating period of history.

Indeed, the book has won accolades from top institutions: O’Shaughnessy won the 2014 George Washington Book Prize, the New-York Historical Society Prize for American History, and the Fraunces Tavern Museum Book Award. The book was also a finalist for the Guggenheim-Lehrman Prize for Military History and has even been translated into Chinese.

Since 2014, O’Shaughnessy has spoken to audiences about his work across the United States, Antigua, and his native England — while keeping up with his day jobs: He’s vice president of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, he’s the Saunders director of the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello, and a professor of history at the University of Virginia.

Grateful American™ Foundation founder David Bruce Smith and Hope Katz Gibbs, executive producer, caught up with O’Shaughnessy recently to hear what his life and work have been like since the acclaim.

Scroll down for their Q&A with O’Shaughnessy.

Scroll down for their Q&A with O’Shaughnessy.

Hope Katz Gibbs: Many Americans are familiar with Colonial history from the patriots’ point of view. Your book is about the British side of the American Revolution.

Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy: The book features 10 major characters — the leading British political and military decision-makers during the war. Far from being buffoons who lost the Colonies because of incompetence, these men were very capable. Here’s what I think is the real essence of this war and why it was lost: the lack of British civilian support for the war as well as the size of its army.

The British forces were an army of conquest, not of occupation. So even though they were able to take every major American city during the war, they could never occupy territory. One of the famous examples of this was in the South after the British took Charleston in 1780 and 1781. Their control of the South imploded soon after as they faced guerrilla-like warfare. The British troops soon became stretched out, their supply lines were cut, and they had to import their food from Britain, 3,000 miles away. As a result, they were never able to entirely feed and supply their army in America, and although no army in the South could significantly oppose them, they were unable to control the territory

Hope Katz Gibbs: You’ve been appointed the first Sons of the American Revolution visiting professor at King’s College London. As part of the Georgian Papers Programme, you’ll have early access to the extensive archive of the private papers of King George III, the British monarch during the American Revolution.

Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy: These papers, which deal with the British side of the war, are not only probably the most important unpublished papers on the American Revolutionary War, but in many cases they have never before even been accessed. Only 15 percent of them have been published and they consist of more than 450,000 pages, not only of George III’s papers, but also of other British officials.

Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy: These papers, which deal with the British side of the war, are not only probably the most important unpublished papers on the American Revolutionary War, but in many cases they have never before even been accessed. Only 15 percent of them have been published and they consist of more than 450,000 pages, not only of George III’s papers, but also of other British officials.

Some of the papers were published during the period of the American Revolution by an editor named Sir John Fortescue, but he was infamously inaccurate — so much so that in the 20th century, British historian Sir Lewis Namier published a book of corrections of errors Fortescue made in his publication of George III’s papers that dealt with just one year!

The other problem is that these papers were never indexed, so historians don’t know exactly what’s in the Royal Archives. It was also very difficult to visit: You had to get written permission, it wasn’t open for most of the week, and they didn’t have wi-fi. They’re now opening up this archive and digitizing it, making available to anyone.

Hope Katz Gibbs: What do you think you will find — or hope to find — in these archives?

Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy: I’m looking at the extent to which George III was involved in devising military strategy. As king, he was very much like the president of the United States. He was commander in chief of the army, and indeed all of the armed forces, and he was supposed to be involved in military policy. He also had a particular interest in the military, and he took great interest in the strategy in America. In fact, the orders for John Burgoyne in his march south from Canada — the disastrous march that ended in Saratoga and proved the turning point of the war — are written in the hand of George III.

Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy: I’m looking at the extent to which George III was involved in devising military strategy. As king, he was very much like the president of the United States. He was commander in chief of the army, and indeed all of the armed forces, and he was supposed to be involved in military policy. He also had a particular interest in the military, and he took great interest in the strategy in America. In fact, the orders for John Burgoyne in his march south from Canada — the disastrous march that ended in Saratoga and proved the turning point of the war — are written in the hand of George III.

Hope Katz Gibbs: Tell us about some of the research in progress at Monticello.

Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy: This year we did a conference in Hong Kong on propaganda and the American Revolution. Next year we’re planning a conference on education in the early republic. We also edit the papers of Thomas Jefferson during his retirement period. These volumes cover the period in which he founded the University of Virginia and his famous retirement correspondence with John Adams, possibly one of the great correspondences of all time. In addition we have about 30 scholars visit on fellowships every year.

Hope Katz Gibbs: From the Revolutionary Era to his retirement, Thomas Jefferson accomplished many things. Did he change his mind on any long-held beliefs about America during his retirement?

Hope Katz Gibbs: From the Revolutionary Era to his retirement, Thomas Jefferson accomplished many things. Did he change his mind on any long-held beliefs about America during his retirement?

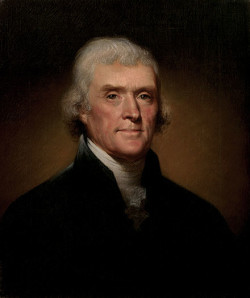

Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy: It’s inevitable that an active politician who’s interested in ideas will contradict himself over the course of his career. Probably the most famous example with Jefferson is his stance on slavery. He’s accused of being a hypocrite for writing that “all men are created equal,” while owning more than 600 slaves during his lifetime. In fact he’d been one of the early people to speak up against slavery, calling it an “abomination.” In his early legal career, he defended free black people who came to court to defend their right to remain free.

In the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson originally included a paragraph condemning the slave trade. In the only book he wrote, “Notes on the State of Virginia,” he called for the gradual emancipation of slaves. He had quite impressive anti-slavery credentials, but later in life, he spoke out on the subject much less. By then the demand for cotton in the Colonies had revived slavery, and Jefferson knew that if he became an outspoken critic of slavery he could never have been elected US president. His opponents in the Federalist party were privately critical of slavery, but none, including John Adams, pushed the issue when in power.

Based on archaeology, we’ve rebuilt some of the slave cabins at Monticello, and we’ve also interviewed more than 200 descendants of the families who lived and worked on Monticello. Slavery is the darkest side of the American Revolution. We celebrate what is best in America and some of the higher ideals, but at the same time, I think there’s a responsibility to talk about both.

Hope Katz Gibbs: How was Jefferson perceived by Americans then and now?

Hope Katz Gibbs: How was Jefferson perceived by Americans then and now?

Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy: He was quite a polarizing figure even in his own lifetime — there were those who detested him, and supporters who hugely admired him. Historian Merrill Peterson showed that Jefferson’s reputation has waxed and waned throughout the 19th century and early 20th century. It probably reached its zenith in the 1940s, 50s, and early 60s when Jefferson became one of the great symbols of freedom during the Cold War.

Then, with the rise of the Civil Rights movement, we start to get a more nuanced view of Jefferson, to the extent that now we almost celebrate his opponents more. This is ironic since of all of the nation’s founders, Jefferson was the most radical — the one who most trusted the idea of government by the people, and the one who was least fearful of the consequences of democracy. Noteworthy Jefferson opponent Alexander Hamilton was wonderful in his own right, but it’s ironic that he has become so popular because he was distrustful of democracy, favoring a much more elitist approach to politics.

Hope Katz Gibbs: What impact do you think Jefferson’s ideas have on the world today?

Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy: He’s still an inspiration. I think he continues to rank as one of the most eloquent writers on the topic of liberty and the dangers of despotism. I’m amazed by how many people abroad read his writings and have been inspired by them. He’s always high on the list of America’s most popular presidents.

Hope Katz Gibbs: What’s next for you?

Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy: I’m writing a book about Jefferson’s founding of the University of Virginia. The first part of the title — “The Illimitable Freedom of the Human Mind: Thomas Jefferson’s Idea of a University” — is a quote of Jefferson’s. He considered founding the university one of the three great achievements in his life and asked that it be listed on his tombstone.

It’s also significant that Jefferson in many ways was very libertarian and yet in terms of education, he advocated radical expansion of government to fund education. He wanted to introduce a public system of education for boys and girls from the earliest ages, which would have created the first truly public education system in the world. He never managed to get that through the local legislature, but in his late 70s, he realized his vision of having a university for the state that he could see from his home at Monticello. He even designed the main campus and the main building, the Rotunda, and creating the University of Virginia was certainly the biggest building project in America at that time.

Order a copy of “The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution, and the Fate of the Empire” from amazon.com.