Frederick Douglass: A struggle to the end

When Frederick Douglass got home on the evening of Feb. 20, 1895, he was energized. A voluble storyteller prone to imitating his characters, the great man walked through the double doors at Cedar Hill, his elegant hilltop home in Washington’s Anacostia neighborhood, bristling to talk about what had just happened to him.

The abolitionist titan had spent hours at a woman’s suffrage meeting at a downtown hall. Despite decades of antipathy between Douglass and the group’s leaders (he had at a critical moment prioritized the vote for African American men over their push to enfranchise white women; they had responded with an openly racist backlash), he was warmly welcomed.

They applauded him, Douglass told his wife after depositing his cane, getting out of his heavy coat and having a quick bite before heading out again. Susan B. Anthony herself had escorted him to the stage and sat beside him. He stayed for hours, immersing himself in their deliberations, kibitzing strategy for yet another freedom movement.

He was thrilled. One week after his 77th birthday (there was uncertainty about his actual age), Douglass was a retired diplomat, an acclaimed author, a revered icon and a wealthy man. Just the day before, his wife told the reporters who would rush to the house that evening, the couple had talked about Douglass’s vigor and his plans to remain in public life for years to come. Here he was, flush with a day full of the righteous drive that had made him, as the next day’s newspapers would put it, “the Most Eloquent and Distinguished of his Race.”

Then, clasping his hands to his chest in a gesture that Helen Pitts Douglass first saw as part of his storytelling stagecraft, he sank to his knees in the front hallway, and then to the floor.

Frederick Douglass was dead.

“It was a shock to everyone, to the world,” said David Blight, a Yale historian and author of the 2018 biography “Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom.”

“What is moving to me is that literally to his dying day, he never stopped fighting for full enfranchisement, for everyone” said Rebecca Traister, who recounted Douglass’s last day in her history “Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger.”

By the winter of 1895, Douglass was a uniquely American giant. His remarkable personal history and unparalleled record of achievement had long before made him an international celebrity: the Maryland slave who seized his own freedom by escaping; the self-taught child who became a philosopher-warrior in the service of liberty for all; President Abraham Lincoln’s conscience; and a moral touchstone for the nation.

Douglass rode his talent for soaring oratory to the top ranks of the abolitionist movement and embraced other radical reform campaigns along the way. He was a thundering voice for emancipation through the Civil War and for suffrage and equal treatment after it. By the 1870s, his fame was such that he became the first black American nominated for vice president, albeit without his approval.

His last years were a time of domestic harmony spent with Helen Pitts, his second wife, a white activist who worked in his office when Douglass was Washington’s appointed registrar of deeds. Their marriage had shocked the nation — and caused Pitts to be alienated from much of her family — but by most accounts their life was one of love and mutual enjoyment. With his dog Frank, a mastiff, they lived on their 15-acre estate high above the sweep of Washington, writing, receiving admirers, playing croquet with the Howard University students Douglass mentored.

“He was quite a storyteller,” said Kamal McClarin, who spends his days at the carefully preserved house as curator of the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site. In the dining room, McClarin points out the wheels Douglass had installed on his chair to make it easier for him to push away when spinning a yarn. “He was known to be very animated and would get up and mock and mimic the people he was talking about.”

It was also a time of rhetorical renewal for the man who had written multiple autobiographies. His later years spent as a political appointee and diplomat had seen an ebbing of his great public activism, Blight said. But toward the end of his life, after a stirring speech at the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, he had returned to the circuit with vigor and a fiery anti-lynching lecture.

“In his 70s, he had found his voice again,” Blight said. “He was scheduled to go speak at another church on the day he died.”

That day started pleasantly with a morning carriage down from Cedar Hill. The Douglasses traveled together as far as the Library of Congress, where Helen stopped for a day of research of her own. Douglass went on to Metzerott Hall on F Street and a meeting of the National Women’s Council.

Newspaper accounts — news of his death filled a third of The Washington Post’s front page the next morning — suggested he hadn’t been expected at the gathering. Douglass had been a champion for women’s suffrage from an early age — he had been the only African American to attend the groundbreaking Seneca Falls Convention for women’s rights in 1848 — but had split with the movement in the late 1860s during the fight to give African American men the vote through the 15th Amendment.

Attaching the woman’s vote to the measure, as leaders of the suffrage movement wanted, would have sunk the effort, Douglass argued. Many, particularly Elizabeth Cady Stanton, responded with racial attacks on Douglass and the notion that African American men would be enfranchised before women.

Still, Douglass remained an advocate for suffrage and those many years later he was greeted at the convention as an honored elder statesman, given a standing ovation and welcomed to the stage.

“I think he was looking for those moments of reconciliation in his later years,” said Blight, who noted that almost all reform movements are riven by fights among the big personalities leading them. “By this time, they had all been through so much it was basically a survivors’ club.”

He stayed until 5 p.m. and was, attendees reported, engaged and energetic. One participant, though, told reporters he seemed to be incessantly rubbing his arm, as if it were “benumbed.”

Yet, according to Helen Pitts Douglass, he was notably eager to recount his day when he returned home that evening. Their servant was out, and the pair stood talking alone at the front of the house.

“We think it was right here,” McClarin said, pointing at a spot between the two front parlors, at the foot of the stairs where Douglass is said to have fallen, stricken by undiagnosed heart disease.

Helen, the horror dawning on her, ran to the front door and called out to the carriage that was even then waiting to take Douglass to his next lecture. One of the men went for a doctor. But by the time one arrived with a “restorative injection,” a great life was over.

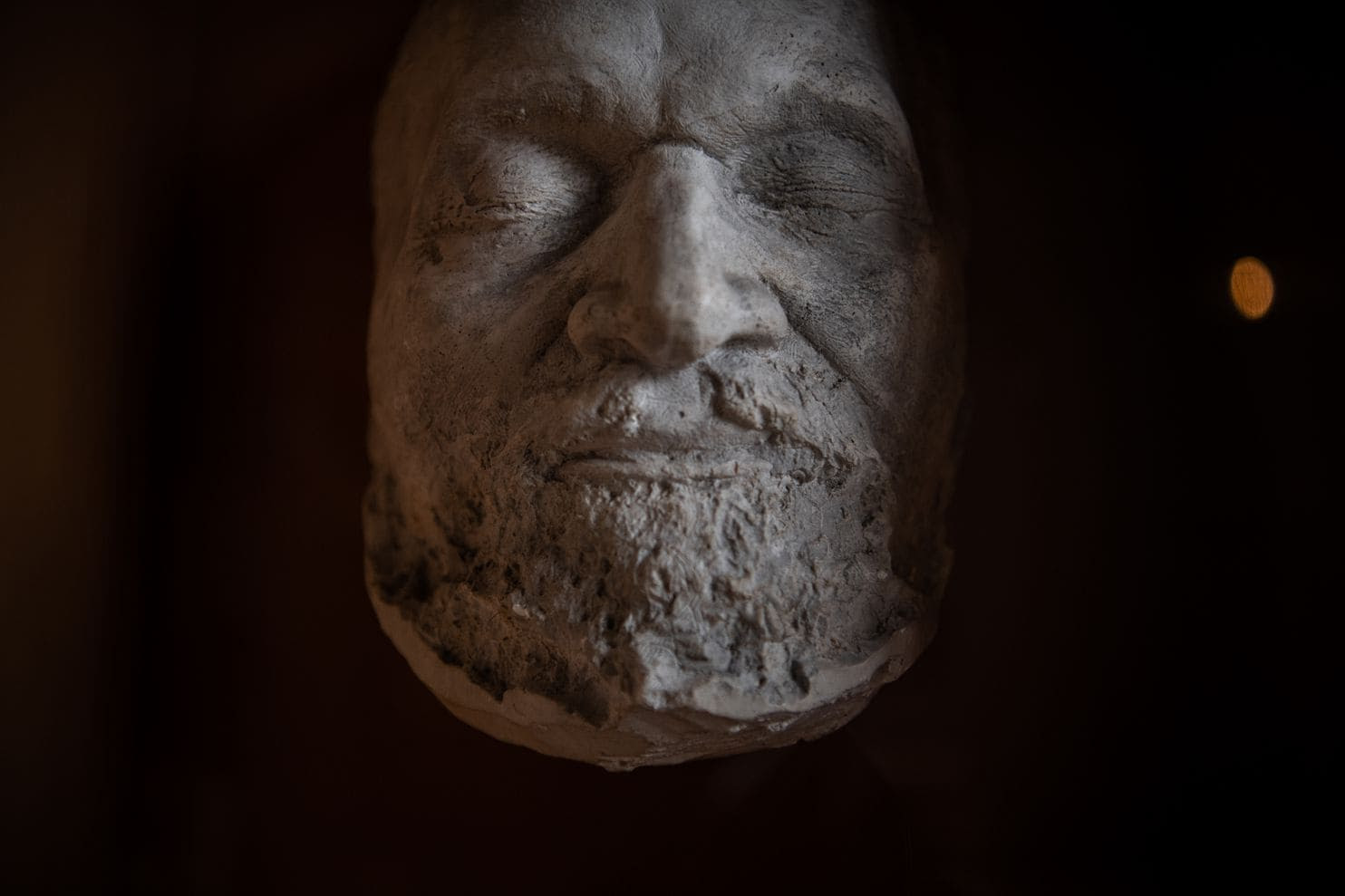

The reporters, who frequently visited Cedar Hill to get Douglass’s thoughts on the issues of the day, now came to hear about his end. A sculptor, Ulric Dunbar, arrived to cast a death mask (which is still on display at Cedar Hill). Someone took a deathbed portrait of Douglass, a final shot of the most photographed man of his century.

The obituaries, eulogies and elegies would continue for months, long after Douglass was buried in Rochester, N.Y., fixing in history the legacy of a man who was waging freedom’s fight, literally, through his final sunset.

Traister, while careful not to assert that Douglass forgave the “fundamentally racist” insults he had endured from the feminist he had alienated, marveled at the man’s commitment to the goals of radical reform, even when it got messy.

“What he understood to the end of his life was the struggle,” she said.

Read story in The Washington Post >>