Franklin Pierce’s

Public and Private Tragedies

Special to the Newsletter

By Michael F. Bishop

Franklin Pierce, the 14th president of the United States, was lucky in his friendships. One of them was with the famed novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne, author of The Scarlet Letter. Hawthorne wrote of Pierce, “He has in him many of the chief elements of a great ruler. His talents are administrative, he has a subtle faculty of making affairs roll onward according to his will, and of influencing their course without showing any trace of his action.” But Hawthorne—like many other novelists since–was a far better writer than a political analyst.

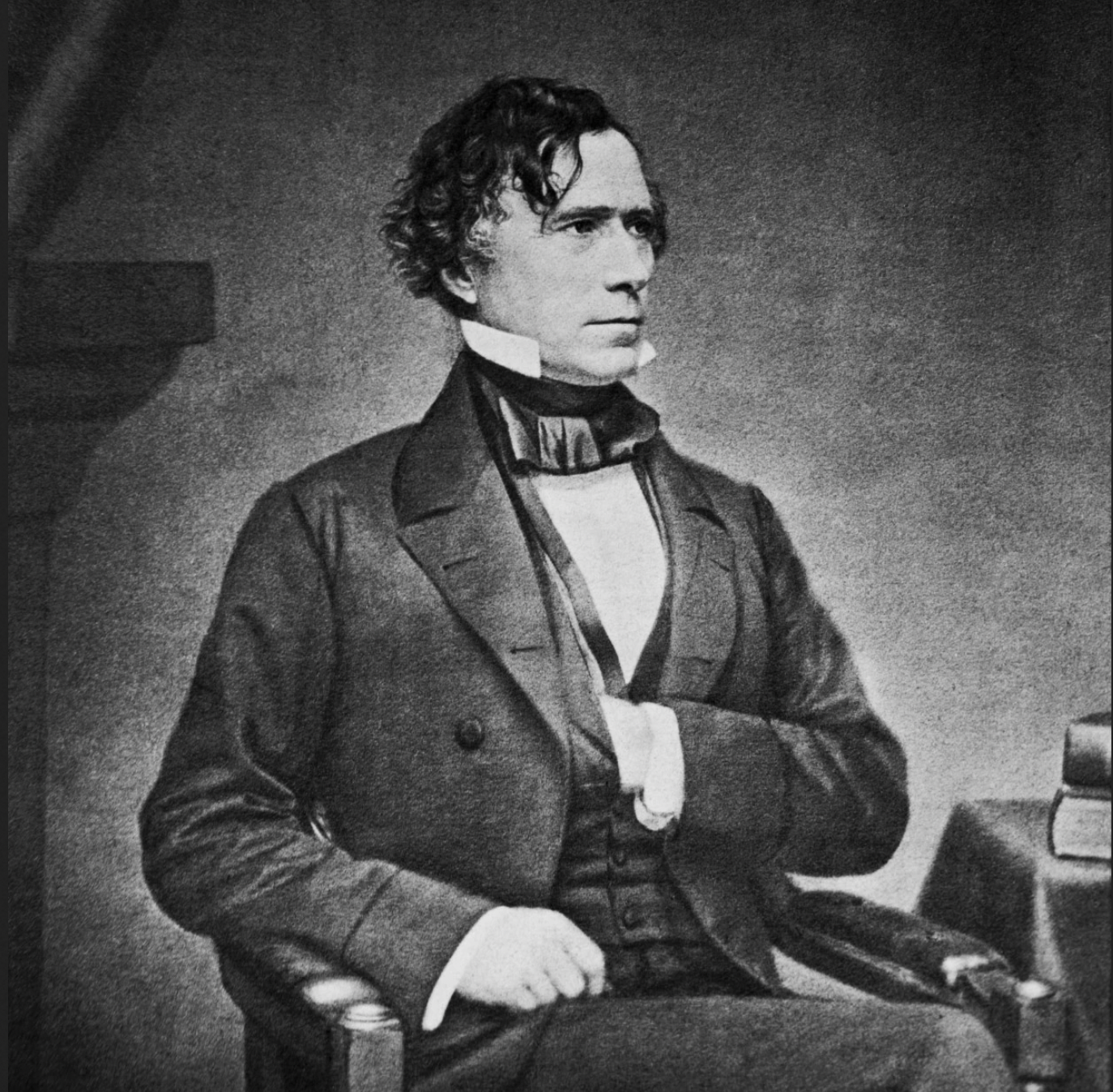

When he was born in New Hampshire in 1804, one of nine children sired by a successful politician and distinguished veteran of the Revolutionary War, Franklin Pierce appeared to have a gilded future ahead of him. Growing up in comfortable circumstances, he was given an excellent education at Phillips Exeter Academy and Bowdoin College. Remarkably handsome, he became a popular and prosperous lawyer, and with the help of his family’s extensive political connections, decided to run for office. He was elected to the state legislature in 1829, and his rise seemed effortless; just four years later, he went to Washington as a Member of the House of Representatives. In 1834 he married the pious Jane Means Appleton, whose serious demeanor and stern sobriety contrasted sharply with her outgoing, bibulous husband. Their married life was darkened by the early deaths of their first two sons.

To the consternation of his gloomy wife, who despised the capital, Pierce loved Washington and its political intrigue. She soon returned home and left Pierce to enjoy the male camaraderie of the city’s boarding houses, where he indulged his ever-growing fondness for alcohol. Though he was born and bred a New Englander, Pierce was a fierce champion of Southern rights. A loyal Democrat, he became known for his passionate denunciation of abolitionism, which he believed posed a mortal threat to the maintenance of the Union. His private opposition to slavery did not impede his progress within the party, and at the age of 32 he became New Hampshire’s junior senator.

In those days, the Senate in those days was a stage for immense political and oratorical talent; Charles Sumner, Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun loomed large in the chamber. Pierce was more dutiful than distinguished, and before his term ended, he resigned his seat to return to his family and law career in New Hampshire. While he remained active in Democratic circles, it seemed his national political career was over.

But the war with Mexico intervened, and Pierce continued a family tradition of joining the army. He was made a brigadier general in 1847, but his military service proved no more distinguished than his senatorial career. Sickness and accidental injuries left him incapacitated for long stretches of the conflict. But as things turned out, it had been enough just to wear the uniform.

When the Democratic National Convention met in Baltimore in 1852 to choose a presidential candidate, Pierce was far from the minds of most delegates. But a seeming deadlock left them casting about for a plausible candidate, and on the 49th ballot they chose the former senator and general from New Hampshire. Though Pierce had given his quiet consent to his name being floated before the convention, he had neglected to mention the possibility to his wife. She was horrified at the prospect of life in the White House, but the weakness of the Whig candidate, Winfield Scott, made it clear she would have to move there.

Until the second inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt on January 20, 1937, American presidents began their administrations on March 4, nearly four months after being elected. Pierce could look forward to a leisurely interregnum to assemble his administration and bask in the public eye before assuming the burdens of office. But his lengthy period as president-elect was immeasurably darkened when his 11-year-old son, Benjamin, died in a gruesome road accident before his parents’ eyes. Thus, it was a shattered Pierce who said in his inaugural address, “You have summoned me in my weakness; you must sustain me by your strength.” This was more than just the customary protestations of unfitness for the office that presidents used to be expected to utter; it was a prophecy.

Pierce was true to his word. A weak and ineffective leader, he fiddled while the country edged ever closer to sectional conflict. While Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois was the chief legislative sponsor of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which opened the possibility of slavery filtering into the western territories, it was Pierce who signed it. This further inflamed the divide over slavery and proved a major landmark on the road to Civil War. Pierce limped to the end of his term, and his party rejected his bid for reelection. He was succeeded by the experienced (but even more hapless) James Buchanan, a fellow northern Democrat who shared Pierce’s southern sympathies. Four years after that, it would fall to Abraham Lincoln—a homelier man than Pierce, but an infinitely greater one—to save the Union that “Handsome Frank” had so imperiled.

Pierce would live for a dozen years after leaving the White House, frequently escaping the cold of New Hampshire for the sunnier climes of southern Europe and the Caribbean. He continued to blame the abolitionists for the strife and bloodshed of the Civil War, and vocally opposed the policies of the Lincoln administration, declaring, “I never justify, sustain, or in any way or to any extent uphold this cruel, heartless, aimless unnecessary war.”

Despite their political differences, the two presidents were united by a common tragedy. In February 1862, Lincoln’s beloved son, Willie, died in the White House at same age as Pierce’s had. In a moving letter to his successor, Pierce wrote, “Even in this hour, so full of danger to our Country, and of trial and anxiety to all good men, your thoughts, will be, of your cherished boy, who will nestle at your heart, until you meet him in that new life, when tears and toils and conflict will be unknown.”

This glimpse of warmth and humanity aside, Pierce’s final years were marked by bitterness and isolation, especially after Jane’s death in 1863. Finally, in 1869, a lifetime of heavy drinking caught up with him and he died—lonely and disillusioned–of cirrhosis–at home in New Hampshire. His death was little noted, and Pierce remains one of the least-regarded American presidents, whose life was marred by tragedy and whose White House tenure was a disaster for the nation.

Michael F. Bishop, a writer and historian, is the former executive director of the International Churchill Society and the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission. He is the author of “We Shall Fight: Churchill’s Greatest Speech,” to be published by HarperCollins.