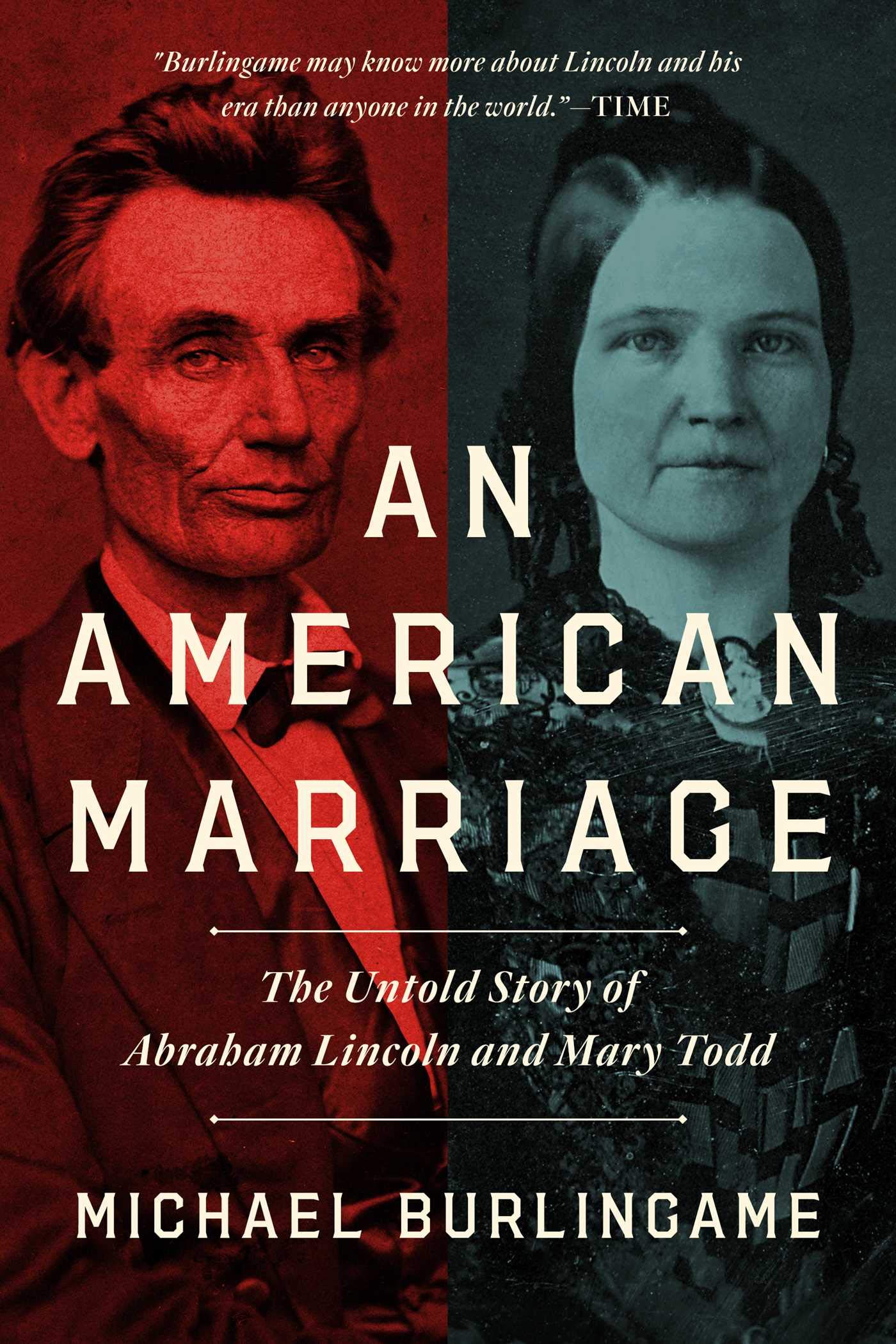

“An American Marriage”

The Untold Story of Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd

by Michael Burlingame

AN AMERICAN MARRIAGE

The Untold Story of Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd

By Michael Burlingame

496 pp. Pegasus Books. $27.95.

Reviewed by The New York Times

Mary Lincoln was not a great first lady. A compulsive shopper, she ran up huge debts that she tried to hide by falsifying bills and misappropriating federal funds. She accepted lavish gifts from men and then lobbied her husband for patronage appointments on their behalf. And she was emotionally unstable, with an explosive temper that was exacerbated by migraines, a debilitating menstrual condition and what was most likely bipolar disorder. She also endured unspeakable tragedies: the deaths of her son Eddie at age 3, her son William at age 11, while the family was living in the White House, and her husband’s after he was shot sitting next to her at Ford’s Theater.

She wasn’t the worst first lady; at least she made an effort. Anna Harrison didn’t set foot in the White House during her husband’s brief presidency. Nor was Mary the least popular, an honor currently held by Melania Trump. In an ordinary decade her failures would likely have faded into obscurity. But Mary presided during the nation’s greatest crisis, and her husband was the nation’s greatest president. Abraham Lincoln’s light would have cast the most successful spouse into shadow.

Most scholars have approached Mary Lincoln’s shortcomings with compassion, excusing all but the worst of her sins on account of her traumas and mental illness. But Michael Burlingame, a leading expert on Abraham Lincoln and a professor of Lincoln studies at the University of Illinois at Springfield, believes this sympathy is misplaced and has obscured a central truth about Lincoln: that his home life was, as Lincoln’s law partner, William H. Herndon, put it, “a burning, scorching hell.” “An American Marriage” forcefully argues this thesis in a series of lively chapters designed to discredit the possibility that the Lincoln marriage was happy, functional or loving.

It isn’t easy to prove that someone else’s marriage is miserable, particularly when neither of the parties will admit as much. Given how few of us fully understand the marriages of our close friends, siblings, even our parents, how is one to unlock the mystery of the Lincoln marriage? Burlingame’s approach is multifaceted. He relies heavily on written accounts by the Lincolns’ contemporaries, most of which were composed after Abraham’s death by individuals unfriendly to Mary, and on journalistic accounts published during the couple’s years in the White House. He also draws on modern psychology. Research into the mental state of abused spouses provides an explanation for why the 6-foot-4 Abraham evinced so little concern over the physical abuse he sustained at the hands of his 5-foot-2 wife (ranging from throwing hot beverages at him to a blow to his face that drew blood). At the heart of this volume is the bold claim that Abraham did not love his wife and deeply regretted his marriage. Burlingame aggressively criticizes scholars who have suggested otherwise by interrogating the objectivity of their sources. Whether his own would withstand similar scrutiny is impossible to determine, given that the volume provides no citations (although an appendix suggests that research notes can be accessed online).

Couples therapists are unlikely to approve of Burlingame’s method. A marriage is the creation of two responsible parties, but the author’s initial assertion that the Lincoln marriage failed because the emotionally distant Abraham and the needy Mary were unsuited for each other quickly collapses under an avalanche of accusations against Mary. The reader learns that Mary was vain, snobbish and pretentious, that she tricked her husband into marriage and then belittled him, that she gossiped, mistreated her servants, asked houseguests to do chores, was both a spendthrift and a pinchpenny, that she didn’t like pets, had delusions of political grandeur, didn’t respond to correspondence promptly, attended séances and sold the milk of the White House cows. The guiding spirit of this volume is Herndon, the Lincoln memorialist whose hatred of Mary was loud and passionate. He wrote of her, “After she got married she became Soured — got gross — became material — avaricious — insolent — mean — insulting — imperious; and a she-wolf.”

Burlingame might have interrogated Herndon’s objectivity, or expressed skepticism about the hearsay and rumors that underlie many of the accusations in this volume. Instead, he conjectures. An anonymous letter to the president accusing Mary of having an affair with a lobbyist named William S. Wood allows the author to infer that Abraham “might have had a possible adultery scandal in mind” when he reportedly expressed concern to Orville Browning about his wife disgracing him. A paragraph later, Burlingame asserts, on equally questionable grounds, that “Mrs. Lincoln may have been unfaithful with others as well as with Wood,” without having established the truth of the Wood affair.

Primary caregivers will note how frequently Mary and Abraham are held to different standards. Mary is dismissed as a negligent mother when she entrusts a 6-year-old with the care of her baby. But Abraham is “not a good babysitter” when he ignores his screaming children and allows one to fall out of a wagon. Mary’s physical disciplining of her children receives censure, but when Abraham beats one of his sons an approving observer notes that he “corrected his child as a father ought to do.” After Burlingame has asserted that the first lady secured patronage appointments by lobbying her husband, he then qualifies his accusation with the note that “her voice counted for little except in relatively minor cases.” To admit that Mary had influence over her husband would open up the possibility that the Lincoln marriage was functional, that Abraham valued her opinion or that Mary’s claims to political power had a basis in fact.

Burlingame goes so far as to assign Mary a certain culpability in her husband’s assassination. Her rude treatment of Julia Grant reportedly prevented Gen. Ulysses S. Grant from accompanying the first couple to Ford’s Theater on April 14, when John Wilkes Booth fired the fatal shot. Had Grant been there, Burlingame asserts, his “own self-protective instincts, honed by long battlefield experience, would have made it unlikely that Booth would have succeeded.” If “An American Marriage” is to be believed, Booth put the president out of his misery.

Amy S. Greenberg, a historian at Penn State University, is the author of “Lady First: The World of First Lady Sarah Polk.”