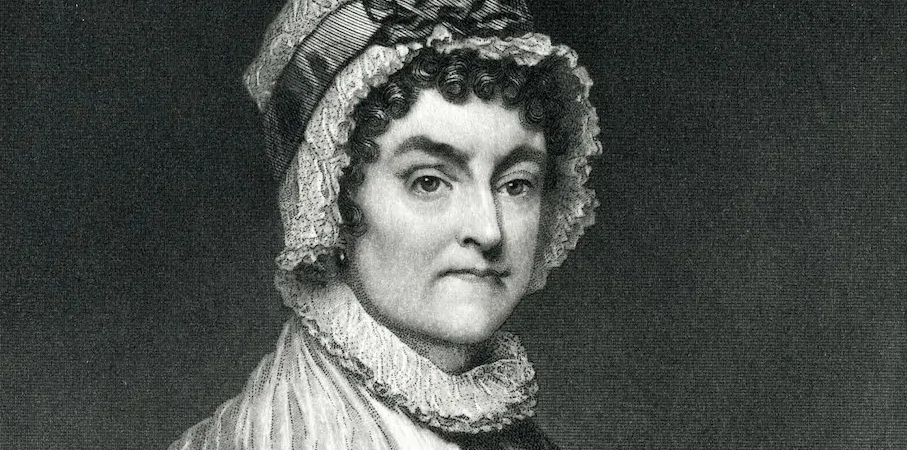

‘A fearsome decision’: Abigail Adams had her children inoculated against smallpox

The future first lady feared inoculation, but she feared smallpox more.

The future first lady feared inoculation, but she feared smallpox more.

It was 1776, and Abigail Adams had decided that she and her four children would seek protection from a deadly epidemic. Her husband, John Adams, was in Philadelphia, where the Declaration of Independence had just been announced.

A smallpox inoculation involved a controversial treatment: infecting the recipient with a mild case of the deadly disease.

“God grant that we may all go comfortably through the Distemper,” Abigail wrote her husband.

At the dawn of the American Revolution, the world was fighting smallpox just as it now is battling the novel coronavirus.

Like the novel coronavirus, smallpox was “a highly contagious virus that is transmitted from contact with an infected person, causing illness,” said Jonathan Stolz, a retired physician in Williamsburg, Va., and author of “Medicine from Cave Dwellers to Millennials.” More than 100,000 people in the colonies died of smallpox. Scientists around the world were desperately seeking to develop a vaccine.

People now are on the brink of receiving vaccines to prevent covid-19, the illness caused by the coronavirus, which so far has killed nearly 300,000 Americans. In 1776, the only medical preventive was an inoculation that had been developed in Boston in the 1720s by Cotton Mather, a Puritan minister, and Zabdiel Boylston, a physician. But the procedure was considered so dangerous that a number of states eventually banned it.

So many people ignored the ban, however, that in June 1776, Massachusetts suspended its prohibition, and many doctors set up shop in Boston to perform inoculations.

Abigail Adams headed to Boston with her four children — 11-year-old Abigail (called “Nabby”), John Quincy, age 9; Charles, age 6, and 4-year-old Thomas. She had the support of her husband, who had gone through the painful process of inoculation in 1764 and wanted his family protected.

It was “a fearsome decision,” wrote presidential historian Feather Schwartz Foster in her book “The First Ladies.” The treatment involved scraping a smallpox-infected serum into the skin. If the procedure were successful, pock marks would occur in about 10 days. The term “small pocks” led to the name smallpox.

Abigail and her children “went ten miles from their home in Braintree to Boston, to be inoculated by Dr. Thomas Bullfinch, an expert at the procedure,” Foster wrote.

Several thousand people had flocked to Boston. “Such a spirit of inoculation never before took place, the Town and every House in it, are as full as they can hold,” Mrs. Adams wrote her husband. “I had many disagreeable Sensations at the Thoughts of coming myself, but to see my children through it I thought my duty, and all those feelings vanished as soon as I was inoculated, and I trust a kind providence will carry me safely through.”

The family was inoculated on July 12. “Our Little ones stood the operation Manfully,” Mrs. Adams wrote. “The Little folks are very sick then and puke every morning, but after that they are comfortable.”

Then came the wait to see whether the procedure had worked. Abigail, addressing her husband as “my dearest Friend,” wrote that Nabby and Johnny were showing signs of the disease as planned but that Tommy wasn’t, so the doctor “inoculated him again today fearing it had not taken.”

By July 29, Mrs. Adams was able to report about herself, “I write you now, thanks be to Heaven, free from pain, in Good Spirits, but weak and feeble.” But she noted that “the smallpox acts very oddly this Season … 3 out of our 4 children have been twice inoculated, two of them Charles and Tommy have not had one Symptom.”

Future president John Quincy was having the easiest case, said historian Foster. But “Nabby Adams was very sick with fevers, terrible body aches, and erupting pustules,” Foster wrote. “Neither Charles and Thomas responded to the inoculation, and it had to be repeated. For Charles, it had to be repeated three times — the last, with a more ‘active’ scraping, ensuring that he would contract the dreaded disease as if he had contracted it naturally.”

Abigail had hoped to complete the entire treatment in three weeks. But the doctors were experiencing a high failure rate, requiring extra time for results. “Every physician has a number of patients in this doubtful state,” she wrote her husband.

John Adams agonized between letters. “I hang upon Tenterhooks” for reports, he wrote. And he was angered to hear about the delays in treatment. In an Aug. 3 letter, he complained that the doctors had taken on too many patients. “No Physician has either Head or Hands enough to attend a Thousand Patients…I wish you had all come to Philadelphia, and had the Distemper here.”

Mrs. Adams wrote that Nabby was so sore “that she can neither walk sit stand or lie with any comfort.” But “at present all my attention is taken up with the care of our Little Charles who has been very bad. The Symptoms rose to a burning fever… and delirium ensued for 48 hours.”

Finally, on Aug. 31, Mrs. Adams reported that a friend had taken all of the children except “our Little Charles who is weak and feeble.” By Sept. 2, Charles, too, was on the way to recovery.

“This is a Beautiful Morning,” Abigail wrote her husband. “I came here with all my treasure of children, have passed through one of the most terrible Diseases to which human Nature is subject, and not one of us is wanting.”

The smallpox epidemic continued to devastate the economy of the colonies and preparations for war against the British. Gen. George Washington, who had recovered from smallpox and thus was immune, was an early advocate of inoculation. In 1777, “Washington had all his troops and incoming recruits inoculated,” author Stolz said. “The government-sponsored mass inoculation was the first of its kind in America.”

Finally, in 1798, the British physician Edward Jenner announced a vaccine, originally using cowpox, that would prevent smallpox. Jenner declared that “the annihilation of the smallpox, the most dreadful scourge of the human species, must be the final result of this practice.” Eventually, smallpox was eradicated around the world.

In 1802, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in Boston unanimously voted to make Jenner a member. A letter of congratulations was sent to Jenner from the academy’s corresponding secretary, smallpox-inoculation survivor John Quincy Adams. In 1825, Adams became the sixth president of the United States.

By then, his mother, Abigail, had died of a different scourge that wouldn’t have a vaccine until the end of the 19th century: typhoid fever.