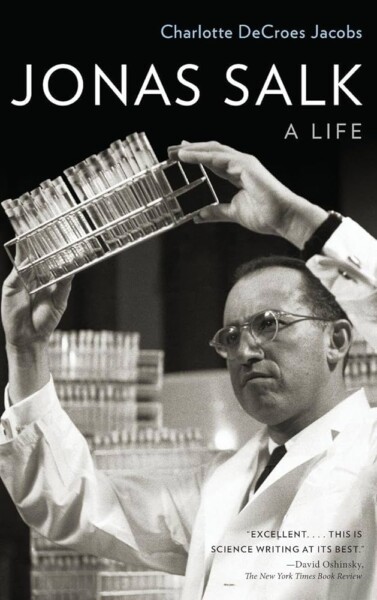

Jonas Salk: A Life

by Charlotte DeCroes Jacobs

Reviewed by Ed Lengel

Jonas Salk: A Life, by Charlotte DeCroes Jacobs. Oxford University Press: 2015.

In our current age, which is rife with skepticism about medicine, science, and its practitioners, it’s hard to imagine a time when great doctors and scientists were viewed as popular heroes. Such a man was Jonas Salk. From humble origins, this shy, self-effacing, likeable man had become known as a miracle worker: the scientist who single-handedly annihilated the scourge of infantile paralysis—polio. Throughout his career, Salk worked tirelessly to gain ground between science and the public; to introduce and familiarize the former to the latter, only to be dismissed as unserious by his peers. His story still has a great deal of resonance, especially as told in this approachable and thoroughly researched biography by Charlotte DeCroes Jacobs.

Born in New York in 1914, the son and grandson of European Jewish immigrants, Salk grew up studious and curios about the human condition, but with no particular interest in science, or medicine. His parents, who had little money to support Salk’s studies, nudged him towards becoming a lawyer, but it quickly became clear that law was not his forte, and as a Jew in the 1930s he had to follow a narrow and difficult educational path that eventually led him toward medicine via the City College of New York and the New York University School of Medicine. Salk’s incredible work ethic and dedication to knowledge—in particular, was a deep-seated desire to benefit humanity—helped him to achieve distinction.

Salk’s devotion to medical research quickly became apparent; he settled into the study of virology. At the beginning of his career, he worked on vaccines for influenza, which had so devastated humanity since its first large-scale appearance at the end of World War I. By the late 1940s and early 1950s, however, polio—in particular—terrified people throughout the world. Stalking seemingly from nowhere, it pounced unseen—targeting children—especially–who could suffer irreversible nerve damage and scar their lies, forever. Sometimes they were depicted in photographs, confined to wheelchairs or gigantic iron lungs—perhaps to survive, perhaps not; perhaps to emerge and walk again, perhaps not. Fortunately for generations to come, and untold millions, Jonas Salk went to work on developing a vaccine for polio at the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis.

Jacobs’s description of Salk’s work on the polio vaccine represents scientific writing at its best, allowing general readers to experience the intrigue, struggle, thrill, and triumph of medical research in a great cause. Vaccine research, indeed, gripped popular attention at the time, fed by publicity over the famous March of Dimes Campaign which provided the funds to underpin it, and gave not just victims, but donors—children, parents, everyone filled with fear and compassion—a stake in the cure. Not even forty years old when he began work in 1952, Salk broke away from other researchers by deciding not to test live, but so-called killed viruses, in order to develop a vaccine that was safe and effective. After initial trials seemed successful, tests went on large try runs on one million children throughout the country. The resulting triumphant approval and use of the vaccine in 1955, wiped out the polio scourge—seemingly for all—and Salk became a household name.

“Young man, a great tragedy has just befallen you,” said the legendary newscaster Edward Murrow to Salk early in 1955. “What’s that?” the scientist asked. Responded Murrow: “You have just lost your anonymity.”

And so he had; but Salk embraced his fame, hoping not to use it for self-aggrandizement, but for the good of humanity. The experience of the hunt for a polio vaccine, he believed, had helped to reduce the differences between scientists and the general public; helping the former to understand the human impact of their work, and the latter to recognize that they, too, could make a difference by supporting research, science, and knowledge. It was an optimistic, positive, message. Salk went even further, given his background, by seeking to cross over science and the humanities—even art—to show how the three disciplines were interconnected.

It was with this vision that he supported the creation of the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California. Tragically, the very organization he founded, and the intellectuals he brought on board to form it, eventually turned on him He was too quiet, self-effacing, not obviously an intellectual—they believed—to belong to their exclusive group. Inevitably, like in many another academic organization, an ivory tower grew, and Salk was excluded. There was unquestionably a great deal of jealousy involved in the intellectuals’ rejection of Salk because he had the instinctive popular touch that they lacked.

Just before he died in 1995, Salk wrote in his journal: “I must find a way to achieve the peace and serenity that I will need to make the most of a rich life experience … that now needs to become a life of greater fulfillment than disappointment. Can I turn all this around in one day? Can I do so in one week, one month, or one year? Can I do so … step by step and day by day. I shall try.” Perhaps this quest to add meaning to Salk’s life work has now devolved in the twenty-first century.

Ed Lengel is an author, a speaker, and a storyteller.