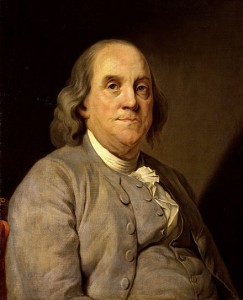

A Genius at Work: Historian Márcia Balisciano Takes Us Inside Benjamin Franklin’s London Home

In the heart of London stands the Benjamin Franklin House, the home where he lived between 1757 and 1775.

In the heart of London stands the Benjamin Franklin House, the home where he lived between 1757 and 1775.

Built circa 1730, the terraced Georgian edifice at 36 Craven Street is the only surviving former residence of one of America’s most famous Founding Fathers. Today it is a vibrant museum and educational facility that features his beloved scientific discoveries, from lightning rods to hydrodynamics. The top floor is the Robert H. Smith Scholarship Centre, which focuses on historical documents including the Papers of Benjamin Franklin, which are sponsored by The American Philosophical Society and Yale University.

What savvy governing agreements was Franklin working out while in London to benefit the United States? Who helped to preserve the c. 1730 residence? Which famous dignitaries have visited the museum in recent years? And what happened to Franklin’s famous home and shop in Philadelphia?

Scroll down for our Q&A with Márcia Balisciano, founding director of the Benjamin Franklin House. She is also the director of corporate responsibility for the global media group Reed Elsevier; previously she served as adviser to the American Chamber of Commerce in Britain, and to the documentary film project “50 Lessons.”

Scroll down for our Q&A with Márcia Balisciano, founding director of the Benjamin Franklin House. She is also the director of corporate responsibility for the global media group Reed Elsevier; previously she served as adviser to the American Chamber of Commerce in Britain, and to the documentary film project “50 Lessons.”

One of 28 international women featured in a book and exhibition for the Federation of American Women’s Clubs Overseas, she is a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. She holds an MA in International Relations from the University of Chicago and a PhD in Economic History from the London School of Economics. Balisciano was made a Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE) in the Queen’s 2007 Birthday Honours List.

Here’s to bringing history to life! — David Bruce Smith, founder, and Hope Katz Gibbs, executive producer, the Grateful American™ Foundation

David Bruce Smith: Benjamin Franklin made his first visit to England in 1725. What inspired the trip, and what was it like for the then 19-year-old to be on his own in a foreign country?

Márcia Balisciano: After serving as an apprentice to his enterprising and demanding older brother James, who was the publisher of Boston’s New England Courant — and who was surprised by and perhaps a bit jealous of his younger sibling’s precocious talents — it was time for Franklin to forge his own way. He traveled to the burgeoning colonial city of Philadelphia with the aim of making his mark as a printer and a publisher. In his autobiography, Franklin describes meeting smooth-talking Pennsylvania Gov. Sir William Keith, whom young Ben so impressed that Keith promised to finance a voyage to England to allow Franklin to purchase the equipment needed to start his press.

No funds were (ever) forthcoming, but Franklin sailed for London anyway. With the help of a wayward traveling companion, writer James Ralph, Franklin took advantage of some of the cosmopolitan delights available in London, such as theatre and books. He unsuccessfully wooed a discarded mistress of Ralph’s and expanded his knowledge about his chosen trade by working in the printing operation housed in 12th century church St Bartholomew the Great, which still stands.

Hope Katz Gibbs: He returned to America in 1726, and eventually built his reputation as a printer, merchant, and civic leader. In Philadelphia, he established the first postal service, public library, and volunteer fire department. Do you have any documentation or stories to suggest that his time in England inspired him?

Hope Katz Gibbs: He returned to America in 1726, and eventually built his reputation as a printer, merchant, and civic leader. In Philadelphia, he established the first postal service, public library, and volunteer fire department. Do you have any documentation or stories to suggest that his time in England inspired him?

Márcia Balisciano: Franklin went on to work at Watts, an even larger printing house in London, where he plied an early interest in civic improvement: “From my example, a great part of them [his colleagues] left their muddling breakfast of beer, and bread, and cheese, finding they could with me be suppli’d from a neighboring house with a large porringer of hot water-gruel, sprinkled with pepper, crumbl’d with bread, and a bit of butter in it, for the price of a pint of beer, viz., three half-pence. This was a more comfortable as well as cheaper breakfast, and kept their heads clearer.” On his return to Philadelphia, he continued this passion for betterment through the Junto, a club of like-minded individuals he established, dedicated to self-improvement and community advancement.

Hope Katz Gibbs: Franklin was vocal about his opposition to taxation without representation. And in 1767, tensions between Britain and the American Colonies worsened as duties were levied on glass, paper, and tea. Even so, he worked toward reconciliation. In fact, in a 1768 letter, he wrote: “I wish prosperity to both sides.” Tell us about that negotiation.

Hope Katz Gibbs: Franklin was vocal about his opposition to taxation without representation. And in 1767, tensions between Britain and the American Colonies worsened as duties were levied on glass, paper, and tea. Even so, he worked toward reconciliation. In fact, in a 1768 letter, he wrote: “I wish prosperity to both sides.” Tell us about that negotiation.

Márcia Balisciano: Colonial concern over arbitrary taxation brewed in the 1760s and first reached a head in 1765 with the Stamp Act, which required Americans to purchase a stamp for an array of goods, from newspapers and contracts to playing cards.

Rumor on the home front had it that Franklin — who returned to England in 1757 to represent Colonial interests, now as a successful printer, publisher, civic leader, and politician — was in favor of the Act, but in fact he gave compelling testimony toward its successful repeal a year later: “If you have no right to tax them internally, you have none to tax them externally, or make any other law to bind them. At present they do not reason so, but in time they may possibly be convinced by these arguments.”

But one unpopular duty gave way to others and culminated in the Boston Tea Party of 1773. At stake was not only political but economic sovereignty. The Colonists were not content with simply supplying raw materials to Britain; they wanted the right to sell their manufactured goods as well. Franklin tried a range of measures to bridge the gap between each side, which included articles, cartoons, spoofs, treatises, and of course, negotiation.

In his “Rules by Which a Great Empire May Be Reduced to a Small One,” he noted in frustration, “A great Cake is most easily diminished at the Edges.”

David Bruce Smith: In his book, “Benjamin Franklin in London: The British Life of America’s Founding Father,” George Goodwin — the Author in Residence at the Benjamin Franklin House — points out that for the great majority of his long life, Franklin was a loyal British royalist. Can you explain?

David Bruce Smith: In his book, “Benjamin Franklin in London: The British Life of America’s Founding Father,” George Goodwin — the Author in Residence at the Benjamin Franklin House — points out that for the great majority of his long life, Franklin was a loyal British royalist. Can you explain?

Márcia Balisciano: Franklin, born in Boston, was Anglo-American. His father came from Ecton, a small village in England’s Northamptonshire, while his mother hailed from Nantucket Island, off the coast of Massachusetts. Yet he thought of himself, as did his contemporaries, as a subject of the king. With his son William he attended the coronation of the 22-year-old King George III in 1761 and had optimism for his leadership.

As he wrote to his friend Samuel Cooper in Boston just six years before the start of the Revolutionary War, “I hope nothing that … may happen will diminish in the least our Loyalty to our Sovereign, or Affection for this Nation in general. I can scarcely conceive a King of better Dispositions, of more exemplary Virtues, or more truly desirous of promoting the Welfare of all his Subjects.” The breach when it came was personal and painful — he was a reluctant rebel.

Hope Katz Gibbs: Franklin is known to have spent many hours in his Craven Street laboratory. What types of scientific discoveries did he make there?

Hope Katz Gibbs: Franklin is known to have spent many hours in his Craven Street laboratory. What types of scientific discoveries did he make there?

Márcia Balisciano: During his long years at Craven Street, Franklin pursued his passion for science and continued his investigations into the nature of electricity. He spliced imagination and practicality and devised a three-wheeled 24-hour perpetual clock and a flexible catheter, and he improved the design of bifocals, among other inventions and investigations.

During conservation, we found remnants of a Franklin stove and damper in the adjoining spaces of his “laboratory,” evidence of his interest in fuel efficiency. He also invented a musical instrument in his London house, the armonica, for which Mozart, (JC) Bach, and Beethoven composed in his own time: nested glass bowls of different octaves, fastened with a steel rod and spun with a treadle to produce the sound of angels. It is still used today, including in the “Harry Potter” theme song!

David Bruce Smith: Although he was known to have enjoyed the company of women during the years that he was in London, Franklin had been married to Deborah Read since 1730. She did not accompany him on his frequent trips to Europe because of a fear of sea travel. In spite of their separations, they remained loyal and supportive partners to each other for nearly half a century. What can you tell us about Franklin’s marriage?

Márcia Balisciano: During his first British foray, Franklin left Deborah behind and she married someone else. As he wrote in his autobiography, “I, by degrees, [forgot] my engagements with Miss Read, to whom I never wrote more than one letter, and that was to let her know I was not likely soon to return. This was another of the great errata of my life, which I should wish to correct if I were to live it over again.”

Her ne’er-do-well husband ran off and was never heard from again, but as Deborah was not divorced or officially widowed, on Franklin’s return to Philadelphia, he and Deborah could not marry officially; she was his common-law wife. During his second sojourn in London, Franklin did write her and she him, replete with spelling mistakes and simple news. Though his dear Debby was not his intellectual equal, she was his stalwart confidante and defender, a brick who stood down a mob come to torch his Philadelphia home during furor over the Stamp Act.

Franklin’s letters home were by turns affectionate and controlling. He has her start building a home on Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street (the architectural footings are all that remain, but it is the site of the US Park Service’s wonderfully rejuvenated Benjamin Franklin Museum) and micromanages its construction from across the ocean.

Mirroring the period of their youth, after Franklin sails in 1764 to England for a third and final time, Deborah waits for his return — but waits in vain. (His second stint in London occurred when Franklin returned there in 1757 as the day’s most well-known Colonial — his fame and wealth staked on his Colonial best-seller “Poor Richard’s Almanack” and pioneering electrical studies — to secure greater financial support from the Penns, proprietary owners of Pennsylvania, on behalf of the Colony’s legislature. That stay in England ended when he came back to Philadelphia in 1762. Some 18 months later, he is sent back to England a third time as an agent for Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Georgia, to seek concessions over taxation without representation.)

Hope Katz Gibbs: Franklin and Deborah had two children: Francis Folger Franklin (Oct. 20, 1732 – Nov. 21, 1736), who died of smallpox at age 4, and Sarah Franklin Bache (Sept. 11, 1743 – Oct. 5, 1808). The couple also raised William Franklin (~1730 – Nov. 17, 1814), Franklin’s illegitimate son, who later became Colonial governor of New Jersey. Did he also live in the Craven Street house? Their reputation eventually soured. Can you tell us about what happened?

Márcia Balisciano: Franklin was a keeper of secrets and never named William’s mother or the circumstances of his son’s birth. William accompanies his father to London in July 1757, and also takes up residence at 36 Craven Street while studying law at the Temple Bar. Franklin was proud of his son’s accomplishments, but they came to hold fundamentally different views on the best course for America. For William, loyalty to the king trumped loyalty to his father.

Though ultimately unsuccessful, Franklin worked tirelessly to find a third way between the interests of the crown and the Colonies (as late as January 1775, he receives former Prime Minister, William Pitt, the Elder, now Earl of Chatham, at Craven Street to try and craft a proposal that can avert war). Unlike his father, when it came time to choose between the country of his birth and his heritage, William picked the latter.

As he wrote to his father in late 1774, “If there was any Prospect of your being able to bring the People in Power to your Way of Thinking, or of those of your Way of Thinking’s being brought into Power, I should not think so much of your Stay. But as you have had by this Time pretty strong Proofs that neither can be reasonably expected and that you are look’d upon with an evil Eye in that Country, and are in no small Danger of being brought into Trouble for your political Conduct, you had certainly better return, while you are able to bear the Fatigues of the Voyage, to a Country where the People revere you.”

David Bruce Smith: Franklin did not leave London to visit Deborah even after she wrote to him in November 1769 saying her illness was due to “dissatisfied distress” over his prolonged absence. In the late 1760s and early 1770s, Deborah suffered a series of strokes that slurred her speech and memory. She died on Dec. 19, 1774. Is there any documentation about his thoughts on this loss? And is her death the reason he returned to America?

Márcia Balisciano: At Benjamin Franklin House, our primary public offering is the Historical Experience, which uses live performance, sound, and visual projection to tell Franklin’s rich London story. One of the most moving moments in the drama comes from his September 1774 letter to her: “It is now nine long Months since I received a Line from my dear Debby. I have supposed it owing to your continual Expectation of my Return; I have feared that some Indisposition had rendered you unable to write; I have imagined any thing rather than admit a Supposition that your kind Attention towards me was abated. … You, who used to be so diligent and faithful a Correspondent. …” Earlier in his life he noted, “a Man cannot in this Life be so perfect as an Angel.” She did not live out the year. If Parliament had heard and accepted the proposal for peace and mutual prosperity crafted with Chatham after Deborah’s death, I suspect he would have remained in England.

Hope Katz Gibbs: Now let’s talk about your wonderful museum, which opened to the public on Jan. 17, 2006. What inspired the restoration?

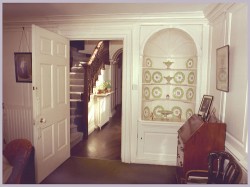

Márcia Balisciano: 36 Craven Street is a historical gem! By some quirk of fate, the only surviving home of Benjamin Franklin, one of America’s most iconic figures, is not in Boston where he was born, not in his adopted city of Philadelphia, nor in Paris where he served, beginning in 1776, as first official representative of the fledgling American government, garnering financial support that led to American success during the Revolution. It is in the heart of London, just steps from Trafalgar Square.

By 1980 the Georgian building was empty and derelict. By the late 1990s, a dedicated management team and substantial fundraising allowed consideration of its future. The starting point was Franklin. As he noted to his great friend, scientist Joseph Priestley, in 1780 (with whom he had spent long hours conversing at Craven Street), “The rapid Progress true Science now makes, occasions my Regretting sometimes that I was born so soon. It is impossible to imagine the Height to which may be carried in a 1000 Years the Power of Man over Matter.” Franklin’s passionate curiosity, his commitment to furthering public knowledge, and his embrace of technology continue to be inspirations.

In addition to the Historical Experience, which relates the history of person and place using drama and digital innovation, our Student Science Centre reveals Franklin’s Craven Street science, allowing children to imagine, hypothesize, and experiment. It also highlights medical history — during conservation we found more than 150 bones, remnants of the anatomy school established with encouragement from Franklin by his landlady’s son-in-law, pioneering scientist William Hewson. All educational provision is free, and we have now served some 25,000 children in the Franklin House and in the community, encompassing in-school fun with Ben’s Traveling Suitcase visits by our education manager, which extends the in-House learning.

David Bruce Smith: How many visitors come through each year? Are they mostly Europeans or Americans? What types of events do you host? And how are you spreading the word worldwide about the colorful Franklin and his causes?

Márcia Balisciano: Approximately 12,000 visit the Benjamin Franklin House each year from around the world. Americans are among our most frequent visitors.

From our top floor Robert H. Smith Scholarship Centre, we plan 40 public events per year, including family days, concerts, and celebrations such as Thanksgiving, held at a city livery hall with three long tables filled with turkeys, pumpkin pies, and trimmings each November. We also hold Franklin-inspired lectures, including our Annual Symposium with speakers that have included a Nobel Prize-winning inventor, the editor of a leading British daily, and prominent diplomats. With our partner the British Library, we are proud of our annual Robert H. Smith Lecture in American Democracy. For the first time, we will hold a Robert H. Smith Lecture this year — featuring award-winning Franklin biographer Walter Isaacson — at the New-York Historical Society on 11 May (for tickets visit: http://www.nyhistory.org/programs/benjamin-franklin-american-democracy-and-innovation).

We get the word out about Franklin and his special London home through our website and social media, and we think he would have loved including Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram!

Hope Katz Gibbs: How do you think the people of Britain best remember Franklin?

Márcia Balisciano: I think Franklin is remembered on this side of the Atlantic as a key US founder and polymath. He is someone they can claim as their own given his long tenure in Britain and his English heritage. I hear from many visitors that Franklin is their polymathic hero! Such adulation for Franklin isn’t new. Even during the Revolution, the British public bought items with Franklin’s likeness, including Wedgewood medallions (1777). The admiration was mutual. As he noted to his young friend, Polly Hewson, daughter of his Craven Street landlady, “Of all the enviable Things England has, I envy it most its People.”

David Bruce Smith: Last, but certainly not least, tell us how you came to work on this project and what the future is for the Benjamin Franklin House in London?

Márcia Balisciano: I have the privilege of being the founding director of Benjamin Franklin House. It is a real labor of love! I was completing a PhD at the London School of Economics wondering what I was to do next when I discovered the project to rescue and open the Franklin House to the public for the first time. I found two Franklin quotes then that have stayed with me since: “Resolve to perform what you ought. Perform without fail what you resolve.”

We have exciting future plans. In this our 10th anniversary year, we aim to introduce new digital offerings in order to reveal new aspects of the Franklin House heritage, attract new audiences, and enhance the visitor experience. This will include a virtual “fly-through” of the house’s Georgian interior showing how the spaces might have looked during Franklin’s tenure. The Virtual Georgian Interior will build on our existing approach, whereby the physical spaces have only one item each to indicate their purpose — place and story are evoked through the performance, sound, and digital renderings. The 18th century rooms are authentic and Franklin would know them if he were to return today.

We will create an updated children’s Historical Experience show featuring newly commissioned illustrations (projections) to enhance young people’s understanding of the Franklin House heritage. They will add color and context to school tours. We also aim to create a new website offering more layered content to help global virtual visitors access the house’s important heritage.

In the longer-term, we plan to add an extension to the back of the building — Franklin Labs — a landmark 21st century addition that will provide more educational offerings, including an immersive timeline of Franklin’s achievements, and special changing exhibitions with innovation as the common strand.

Thank you so much for your time, Márcia! It is a pleasure to learn about Franklin and his London home. We look forward to coming over for a visit!

For more information, visit: www.benjaminfranklinhouse.org

Location Information

Tours

Saving Mount Vernon Tour • Weekends 3:30-4:30pm

Where: George Washington’s Mount Vernon Estate

Where: George Washington’s Mount Vernon Estate

3200 Mt Vernon Memorial Hwy Alexandria VA 22309 • (800) 429-1520 • mountvernon.org • Click here for directions.

Details: During this one-hour tour, visit the rarely seen Mansion basement and wander the historic area to learn of the heroics of the estate’s caretakers during the Civil War, and the robust efforts of many over the century and a half that followed.

The Saving Mount Vernon Tour is available on weekends only from April through October. It is offered at 3:30 pm with a maximum of 20 people per tour. The tour lasts approximately 1 hour and requires walking. A portion of the available tickets are offered in advance. The remainder are sold at the ticket window the day of the tour. Tickets are required for each person on the tour. The tour is sold-out if the date desired does not allow you to add it to your shopping cart. (more…)

Lincoln’s Cottage Tours • Daily, 10am-3pm

Where: Lincoln’s Cottage at Soldiers’ Home

Where: Lincoln’s Cottage at Soldiers’ Home

Rock Creek Church Rd NW & Upshur St NW Washington DC 20011 (202) 829-0436 • lincolncottage.org • Click here for directions.

Monday – Saturday

Visitor Center: 9:30 AM – 4:30 PM • Cottage Tours: First tour at 10 AM • Last tour at 3 PM

Sunday

Visitor Center: 10:30 AM – 4:30 PM • Cottage Tours: First Tour at 11 AM • Last tour at 3 PM

Holiday Hours

Closed on Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Day, and New Year’s Day.

Open on Christmas Eve between 9:30 am and 1:30 pm, last tour begins at 12 pm.

Cottage Admission and Tours

Admission to the Cottage is by guided tour only and requires a tour ticket. Advanced ticket purchase is strongly recommended, and weekend tours often sell out completely. Unreserved tour tickets are available on a first come, first served basis. Tours begin in the Visitor Education Center and last approximately 1 hour from start to finish.

For ticket prices and to purchase a ticket, click here.

For more information on our tours, click here.

Upcoming Events

Remaking the American Patient: How Madison Avenue and Modern Medicine Turned Patients into Consumers

Featuring Nancy Tomes

Where: This program will be held at the Reading Room in Bryant Park. The Reading Room is located on the 42nd Street side of the park between 5th and 6th Avenues. Look for the burgundy and white umbrellas.

When: Wednesday, August 23rd, 2017 | 7:00 pm

Details: In collaboration with the New-York Historical Society, the Bryant Park Reading Room presents a series of free lectures on popular topics including the Supreme Court, the Cold War, presidential biography, and more.

From the early 20th century, when the modern American healthcare system was beginning to take shape, through the present day, aggressive advertising and marketing has played a critical role in shaping how medical professionals and patients alike approach treatment options. As our contemporary political leaders continue to debate how to ensure citizens have access to healthcare, historian Nancy Tomes examines the impact of rebranding patients as “consumers” and turning health insurance and the latest drugs into “must-have products.”

Nancy Tomes is Distinguished Professor of History at SUNY Stony Brook and the author of Remaking the American Patient: How Madison Avenue and Modern Medicine Turned Patients into Consumers, which was awarded Columbia University’s 2017 Bancroft Prize in American History and Diplomacy.

Cost: Free, first come first served.

Click here for more information.