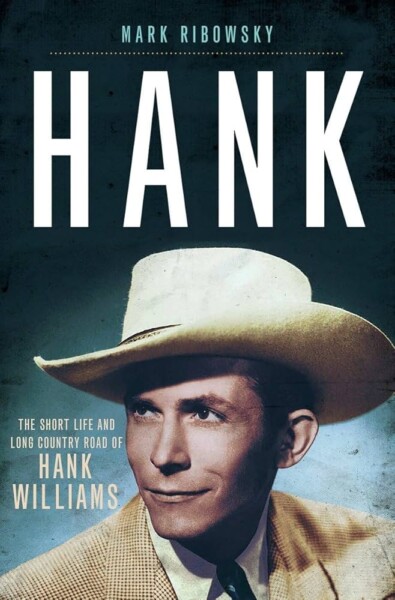

Hank: The Short Life and Long Country Road of Hank Williams

by Mark Ribowsky

Hank: The Short Life and Long Country Road of Hank Williams, by Mark Ribowsky. New York: Liveright, 2017.

Reviewed by Ed Lengel

Hank Williams was a well-known star in country music—and other genres—from songs that were recorded by a throng of contemporary artists, like Tony Bennett, Ray Charles, and The Rolling Stones; Roy Orbison, Dolly Parton, Fats Domino; Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash, and Carrie Underwood. Musicians and songwriters like Bob Dylan, have also acknowledged the influences of Hank Williams, Jr., and Hank Williams III on their music.

Hank Williams, Sr., however, is sometimes remembered in less positive ways. The oldest Hank was an acute alcoholic, and a drug addict who was supplied by charlatan doctors angling to earn a quick fee from a celebrity. He became legendary for showing up drunk at public performances—or not appearing; for raucous, violent, and semi-public battles with his two wives, Audrey and Billie Jean.

A tormented person, Williams died from the cumulative effects of some combination of drugs and alcohol—to say nothing of heavy smoking that weakened his heart—in the back seat of his Cadillac early on New Year’s Day, 1953, at the age of twenty-nine.

Beneath all the celebrity and tragedy, however, there was real, raw talent. Sports and music writer Mark Ribowsky tries to get at the original Hank, by highlighting his brilliance, in this well-written, but flawed biography. Like other talented people, it’s next to impossible to pinpoint the thing that fired up his creativity. Hank Williams was a poor Alabama country boy from a broken family who had to scrape to survive by shining shoes, selling newspapers, and signing up for odd jobs. Inspired by the so-called hillbilly music that he heard on the radio, and by black blues musicians such as Rufus Payne (“Tee Tot”) who plied the Deep South’s backcountry roads, Hank discovered that he loved to sing and play the guitar—even though he didn’t play it much. He was barely educated; he quit school early, but he loved to make music.

Plagued by poverty and surrounded by fighting family members and suffering from an early age from chronic physical pain caused by an undiagnosed severe birth defect that twisted his back, Williams centered his writing on pain: loneliness, loss, conflict—and above all—wounded love. As he wrote them, his songs were unpolished, illiterate, and poorly structured: but they were authentic. And Hank, with a naturally penetrating voice and a hard stare that reinforced the words’ power, had the talent to deliver them. Performing in public, in fact, was where Williams felt most in his element: from street singer to honky-tonk performer, and from high school auditoriums to huge arenas, he always felt most at home, most himself, on stage.

It took many years—not long after World War ll—when he was in his early twenties, for Hank to get noticed by the recording industry in Nashville, and it took even longer for him to get acceptance from the Grand Old Opry. Embracing him hesitantly, and worried by his patent emotional instability and substance abuse issues, music executives were shocked by the spectacular success of Lovesick Blues; Cold, Cold Heart; Move It On Over; Hey Good Lookin;’ Honky Tonkin’ and many more. In the studio, producers were able—to a limited extent—give his writing and delivery the polish it needed to come out on records, and especially in jukeboxes of the era, in style. Still, Hank always preferred to be out on the street singing and it was hard to pin down. While his songs made him immensely wealthy, he squandered his fortune.

Hank is a well-written biography, and the human subject is immensely sympathetic and compelling. Amalgamating the many biographies, personal accounts, and media pieces that have been written about Hank Williams over the years, it’s a readable and fairly full treatment of the subject. Ideally, though, the role of a good biographer is to spotlight his or her subject, bring it fully into focus, reveal the inherent human fascination, and then get out of the way. Essentially, a good biographer is invisible, careful not to obscure the subject. Ribowsky hasn’t mastered that particular skill; often he draws the reader’s attention away from Hank and onto himself by interceding his personal political opinions, or subjective thoughts about good or bad music and musicians (strangely, he seems largely to despise country music), and especially dealing out his views on the people in Hank’s tragic life—especially the women, whom Ribowsky particularly seems to dislike. Those flaws aside, Hank remains a fascinating study of one of the most talented, and tragic figures in American music history.

Ed Lengel is an author, a speaker, and a storyteller.