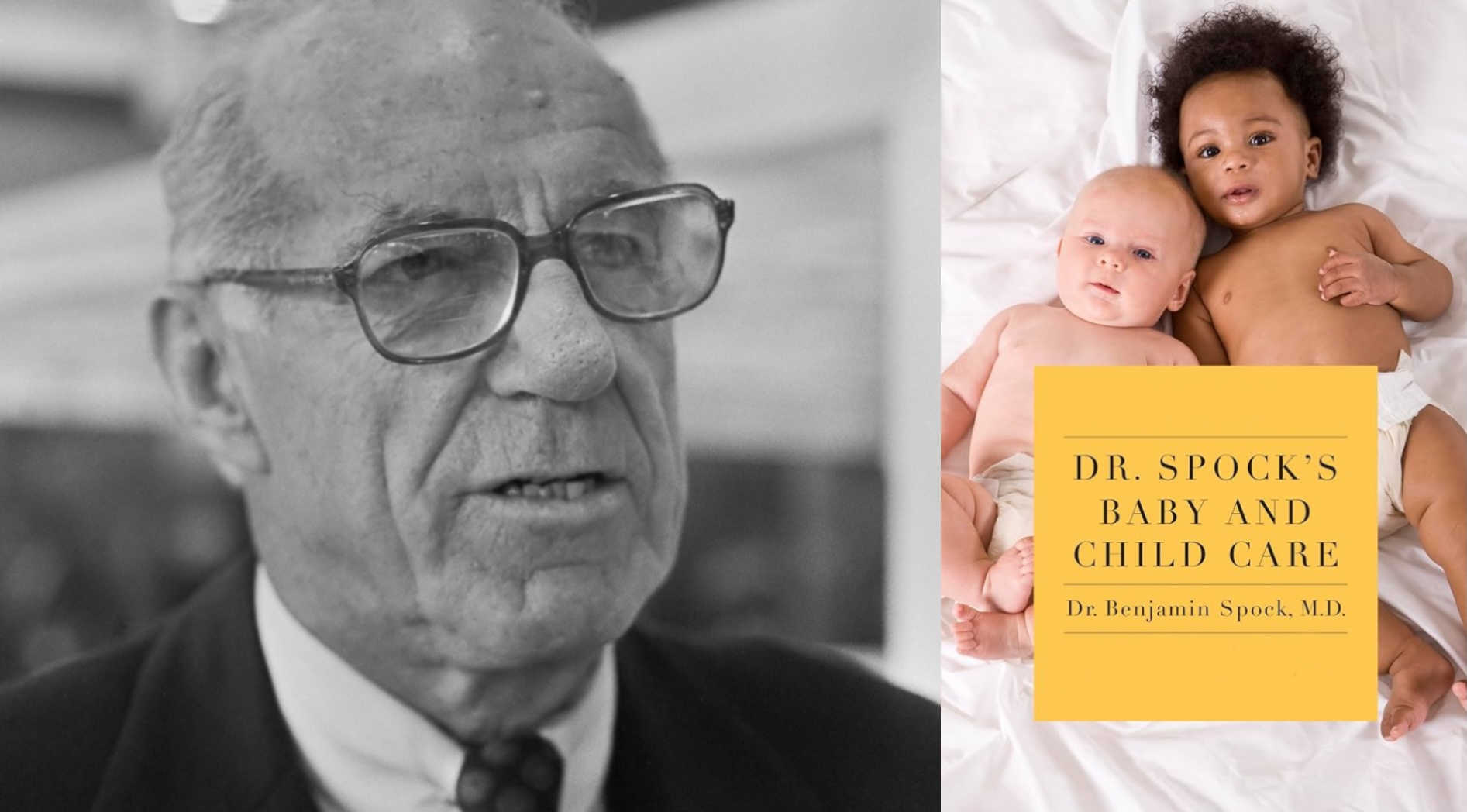

“Dr. Spock”: Benjamin McLane Spock

Special to the Newsletter

by Michael F. Bishop

Benjamin Spock, famously known as Dr. Spock, was one of the most influential figures in 20th-century American parenting and social activism.

Benjamin McLane Spock was born on May 2, 1903, in New Haven, Connecticut, the eldest of six children from a prosperous family. His father, Benjamin Ives Spock, was a conservative railroad lawyer, while his mother, Mildred Louise Stoughton, came from a distinguished background and exerted a profound influence on his views about child-rearing. His early life blended academic rigor with athletic prowess. He attended Phillips Academy and graduated from Yale University in 1925; there, he excelled in rowing and helped the U.S. team secure a gold medal in the men’s eight at the 1924 Paris Olympics.

Afterwards, he enrolled at Yale Medical School, transferred to Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, and finished first in his 1929 class. While practicing as a pediatrician in New York City, Spock grew dissatisfied with what he considered rigid, authoritarian approaches to childcare prevalent in the early 20th century. Influenced by Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis, he began emphasizing children’s emotional needs, family dynamics, and psychological well-being.

In 1946, he published his first book, The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care. Its opening line, “Trust yourself. You know more than you think you do,” set its revolutionary tone. He advised his readers that the “more people have studied different methods of bringing up children the more they have come to the conclusion that what good mothers and fathers instinctively feel like doing for their babies is the best after all.” Spock urged parents to show affection, respond to babies’ cues, and avoid overly strict schedules or discipline. He advocated treating children as individuals deserving respect, rather than miniature adults to be “broken” through harsh methods common in prior generations. The book rejected fear-based tactics, like letting infants “cry it out,” and promoted nurturing over regimentation. The impact was immediate and immense. It sold 500,000 copies in its first six months, and 50 million by Spock’s death. It became the bible for postwar parents, especially during the Baby Boom, shaping how millions brought up their children. Spock’s permissive-yet-responsible approach is credited with humanizing parenting, encouraging emotional bonds, and fostering self-confident generations. Critics later blamed it for “permissiveness” linked to 1960s youth rebellion, but Spock consistently denied advocating indulgence.

Spock also became a prominent activist. In the 1960s, he opposed the Vietnam War, nuclear proliferation, and militarism, arguing that nurturing healthy children was pointless if society sent them to die in unjust conflicts. He marched with Martin Luther King Jr., co-founded anti-war groups, and in 1968 he was convicted of conspiracy to counsel draft resistance; the verdict was overturned on appeal. Four years later, he ran for president on the People’s party ticket.

Later editions of his book reflected evolving science and social changes; he addressed shifting gender roles (earlier versions assumed mothers as primary caregivers) and revised his advice over time. One controversy involved his early (and disastrous) recommendation of prone sleeping for infants, common then, but later linked to increased SIDS risk; he updated guidance as evidence emerged, but the damage was done. In 1968, he admitted that, partly thanks to his book, “Parents began to be afraid to impose on the child in any way.”

Spock remained active into old age, co-authoring a memoir, Spock on Spock, and continued to lecture. He died on March 15, 1998, at age 94 in La Jolla, California, but his dual legacy endures: the “baby doctor” who revolutionized child-rearing by promoting empathy and instinct over dogma, and the activist. His work bridged medicine, psychology, and politics, which influenced parents and—broader cultural attitudes–toward nurturing human potential.

Michael F. Bishop, a writer and historian, is the former executive director of the International Churchill Society and the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission.