“Bound to be True”:

Hans Brinker by Mary Mapes Dodge

Special to the Newsletter

by Michael F. Bishop

Ravaged by the Civil War that had just ended, with 750,000 soldiers never to come home and a beloved president murdered in the moment of victory, the United States needed a pleasant distraction in 1865. It received one in the unlikely form of a children’s novel about a young boy in the Netherlands determined to win an ice-skating race.

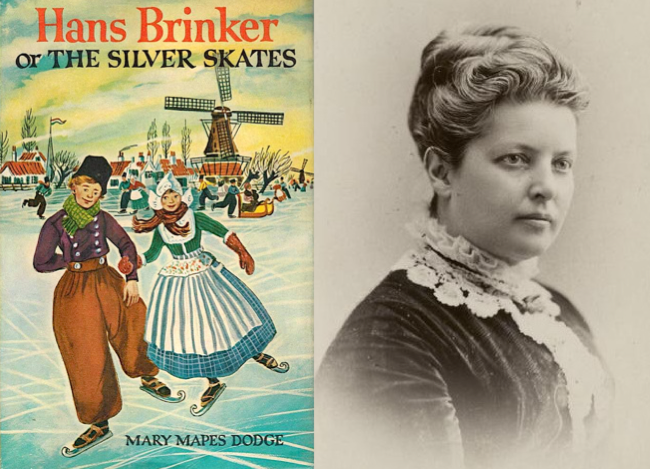

Hans Brinker, or The Silver Skates was written by Mary Mapes Dodge, a native of New York City born in 1831, the daughter of an illustrious professor of agriculture. She was educated at home and showed an early gift for writing. But a romance with a lawyer led to a brief, ill-starred marriage. After they had two children, her husband left her, and died soon after. Dodge raised her boys with the help of her large and generous family and took up her pen to try to make a living. It was a fortuitous choice, and fame and fortune were soon to follow.

She began her literary career as a magazine editor, working with her father and establishing a reputation as a talented manager and businesswoman. She was a prolific writer of short stories for children, who made her reputation with Irvington Stories of 1864. But the following year she would achieve her greatest success.

Set in the early 19th century, Hans Brinker was the fruit of extensive research by the author, who read widely and lived among the descendants of settlers in what had once been the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. She had developed a fascination with Holland, of which she was to write, “There is not a richer, or more carefully tilled garden spot in the whole world.” Of its people, she observed, “There is not a braver, more heroic race than its quiet, passive-looking inhabitants.” She conceived a tale of moral uplift about a young boy determined to participate-along with his sister-in a speed skating race. Hans and his family are poor but proud and dignified, and Hans resolves to earn enough money to buy steel skates for his sister and himself. Only then would they have a chance in the race; their own wooden skates would never do.

Hans succeeds in buying his sister a pair of steel skates, but their father is unwell, and Hans decided that rather than buying skates for himself, he should pay for a medical procedure to bring their father back to health. The father’s condition is acute; after a serious fall he suffered what we would now call subdural hematoma. Dodge’s description of the symptoms is remarkably detailed and astute. Hans begs a prominent surgeon to help save his father and offers him a modest payment for his services. But the surgeon is accustomed to earning far higher fees and wallowing in grief after the loss of his wife, he seems disinclined to help. But his heart is touched by the determination of Hans to save his father, and he agrees to perform a risky operation free of charge.

In a sort of benign chain reaction, one good deed follows another, and all the characters emerge happier than before. The surgeon saves Hans’ s father and the family’s financial stability is restored. Hans buys his steel skates and enters the race but sacrifices victory to help a friend win instead. His sister wins the girls’ race and goes home with a valued prize: a pair of silver skates. Hans may not have won on the ice, but he scores an even greater prize: the surgeon who saved his father guides him into a successful medical career of his own. As a tale of moral uplift, it was hard to beat. As Hans reflects in the novel, “I am not bound to win, but I am bound to be true. I am not bound to succeed, but I am bound to live up to what light I have.”

As if to reinforce the moral of self-sacrifice, Dodge includes in the novel a self-contained story called “The Hero of Haarlem” about a young boy who comes across a dangerously leaky dyke and plugs it with his finger. “Ah!” he thought, with a chuckle of boyish delight, “the angry waters must stay back now! Haarlem shall not be drowned while I am here!” Determined to prevent a catastrophic flood, the boy braves the cold all night until he is discovered the following day. This humble tale-which had been told in various forms long before Dodge popularized it-is a universally recognized story of courage and determination.

Only 34 when Hans Brinker was published, Dodge became a literary celebrity. Her sales that year were exceeded only by those of Charles Dickens. She later became the editor of St. Nicholas Magazine and persuaded some of the most distinguished writers–then–to be contributors; one was Rudyard Kipling– who at Dodge’s urging– wrote The Jungle Book.

After a life of splendid literary achievement and considerable wealth, Mary Mapes Dodge died in 1905 at the age of 74. She was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in New Jersey, not far from her beloved New York. Her reputation is secure, and the 20th century saw several film and television adaptations of her most famous story, which has never gone out of print.

Michael F. Bishop, a writer and historian, is the former executive director of the International Churchill Society and the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission.