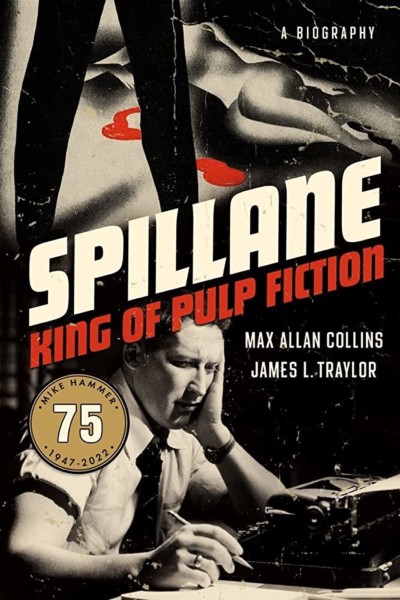

Spillane: King of Pulp Fiction

by Max Allan Collins and James L. Traylor

Reviewed by Ed Lengel

Spillane: King of Pulp Fiction

by Max Allan Collins and James L. Traylor

Mysterious Press, 2023

When my working-class father served in the U.S. Navy during the Korean War, reading was still the dominant pastime for most service members. Recounting his time on shipboard, he told me how his fellow sailors usually had a paperback novel in hand while waiting in the chow line. Eager to educate himself, my dad read works by authors like Dickens and Dostoevsky. Meanwhile—he remembered with disgust—the other sailors leered over dog-eared novels by Mickey Spillane.

Seventy years ago, Spillane was the dominant figure in American popular fiction. By the mid-1950s, his hard-boiled mystery novels were selling second only to Agatha Christie. No one else came close. All this, too, in an era that is remembered today as stuffy and strait-laced. Where other thriller writers only hinted, Spillane reveled in graphic depictions of sex and violence, leading fellow hard-boiled author Raymond Chandler to deride his books as “nothing but a mixture of violence and outright pornography.” By the time Spillane’s popularity reached its peak, however, Chandler’s time in the limelight had long passed, as had that of fellow great Dashiell Hammett. For the generation that fought World War II and Korea, and faced the uncertainties of the Cold War era, no one captured their mentality better than Spillane, who served as a fighter pilot during the war.

Spillane’s first six novels, published between 1947-1952, sold better than anything else he ever wrote: I, the Jury (1947); My Gun is Quick (1950); Vengeance is Mine! (1950); One Lonely Night (1951); The Big Kill (1951); and Kiss Me, Deadly (1952). Born in 1918, and less than thirty years old when his first hit novel was published, Spillane peaked fast. Yet he remained a high-profile figure until his death in 2006–despite his odd personality and propensity to disappear for years at a time. Some of his continued popularity had to do with television serializations from the 1950s to the 1980s, with actors as diverse as Darren McGavin and Stacy Keach playing his protagonist, Mike Hammer; along with some self-mocking cameo appearances on other media, including beer commercials.

Fundamentally, though, Spillane’s ongoing relevance may have had most to do with his authenticity. For all their brilliance, and their grounding (like Spillane) in the popular pulps, Hammett and Chandler were alcoholic literary dilettantes who aspired in some way to merge deep artistic observations on the human condition with their writing. Other popular mystery writers, whether in the hard-boiled American tradition or in the English puzzle-plot style, frequently expressed themselves through quirks of style and character. Spillane wasn’t interested in any of that. His style was raw, direct. “When you’re writing a story,” he explained, “think of it like a joke. What’s a great punch line? Get the great ending then write up to it.” In writing up to his endings—which are always spectacular and viscerally satisfying—Spillane expressed basic feelings and concepts like desire and vengeance. There’s a clear tinge of sadomasochism in much of his writing. And yet he wasn’t without depth. As for much of his generation, the need for simple, direct, and violent answers often belied the complexity of the problems facing them.

Collins, also a prolific mystery/thriller writer, and Traylor, an expert in the pulp fiction genre, are naturals to write this–the first full-length biography of their subject. Indeed, their connections to Spillane and his family date well back into his lifetime, so that they have access and insights into his complicated life history and personality. Collins was Spillane’s literary executor. The drawbacks to the authors’ closeness to their subject are fairly obvious, in that their biography reads—at times–more like an extended fanzine piece than a balanced appraisal of his work. For an understanding of his seemingly self-contradictory relationship with religion (he became a Jehovah’s witness and door-to-door proselytizer), and his volatile personal life (he was married three times), nobody is better-equipped than Collins and Traylor to provide useful observations. Collins’s skills and stylistics as a writer, indeed, nicely match Spillane’s. Augmented by a rich appendix that includes Spillane’s observations on his life and writings and other interesting materials, Spillane: King of Pulp Fiction is a must-read for fans of the hard-boiled genre, and indeed for anyone interested in the nuances of the American popular consciousness in the mid-Twentieth Century.

Ed Lengel is an author, a speaker, and a storyteller.